Editor's Note: This story was updated Jul 21, 2017, with comments from Tina Tan, MD, MPH, New Jersey state epidemiologist.

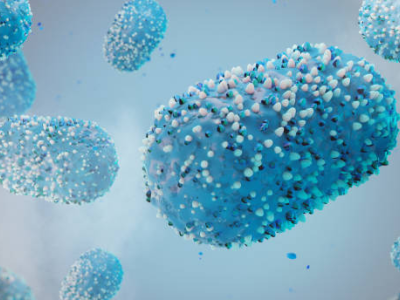

In June 2016, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a clinical alert about an emerging multidrug-resistant fungus causing serious and frequently deadly invasive infections in healthcare settings around the world. The warning was intended as a message to healthcare providers to keep an eye out for Candida auris, which at that point had been found in only a handful of US patients.

More than a year later, the CDC has identified 98 clinical C auris infections in nine states, some of them dating back to 2013, and the fungus has been isolated from an additional 110 patients. That's not a lot, but it's more than CDC officials wanted to see.

"We were really hoping it wasn't here yet, to be honest with you," Tom Chiller, MD, MPHTM, chief of the Mycotic Diseases Branch at the CDC, said in an interview.

Gaining hospital footholds

Candida infections are not uncommon in US hospitals, and they're often associated with high morbidity and mortality. But C auris is different, and it doesn't act like a "typical Candida," Chiller said. Most Candida infections are isolated incidents that occur in patients who carry the yeast in their gut. But what Chiller had learned from his conversations with colleagues in countries like Pakistan and the United Kingdom was that C auris was being transmitted in hospitals.

"That's what caused us to put out the alert," Chiller said. "That was enough evidence to push us over the edge and say, 'yeah, this is definitely a hospital-transmitted organism.'"

So far, C auris appears to be following that pattern in the United States, with clear indications of hospital transmission. While six states have reported only one clinical case, New York and New Jersey have reported 68 and 20, respectively, and whole-genome sequencing has revealed that the isolates within each state appear highly related to one another. Furthermore, the epidemiology indicates that many of the New York and New Jersey patients had overlapping stays at interconnected long-term–care facilities and acute care hospitals.

"To say that transmission is occurring in these settings is definitely the case," Chiller said.

That's confirmed by Tina Tan, MD, MPH, New Jersey state epidemoliogist. "Among our cases...what we're commonly seeing is that there has been healthcare exposure," Tan said in an interview.

Hospital transmission is occurring because C auris likes to stay on skin and is hard to kill when it gets on hospital surfaces. And once it gets into a healthcare facility, it tends to stay. "It's a lot more challenging once it's got a foothold," Chiller said.

But what's not clear is exactly how the fungus is being transmitted, whether patients are acquiring it from hospital bedding or bed rails, for example, or from healthcare workers who've had contact with infected or colonized patients. "We know those are all ways in which typical hospital bacteria is transmitted, so we're tackling them all," Chiller added.

In response, the CDC is recommending that all infected or colonized patients be placed in a single-patient room under standard and contact precautions, and that those rooms are disinfected daily. The agency also recommends screening close contacts of C auris patients for potential colonization and informing receiving healthcare facilities when an infected or colonized patient is being transferred.

Tan said her department is also focusing on opportunities to improve and reinforce hand hygiene in affected facilities, not only among staff but also among patients and visitors. "That's really important as well, to ensure that visitors are aware of some of the considerations related to infection control and hand hygiene," she said.

Concerns over high resistance

CDC investigators have also found worrisome evidence of another trend seen in international C auris cases—resistance to the three major classes of antifungals used to treat Candida infections.

In the May 19 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), investigators reported that antifungal susceptibility tests of the first 35 clinical isolates showed that 86% were resistant to fluconazole, 43% were resistant to amphotericin B, and 3% were resistant to echinocandins.

Chiller called the evidence of multidrug resistance "super concerning."

Preventing spillover to healthier populations

Also unclear is just how deadly the fungal pathogen is. C auris, which was originally identified in the ear of a patient in Japan in 2009, can cause serious invasive infections that affect the bloodstream, heart, brain, ear, and bones, and Chiller said the mortality rate has been high. But to this point, the cases have involved patients with multiple underlying health conditions, which makes it difficult to know whether the infection is killing patients.

"These patients are very complicated, so it's hard to tease apart," Chiller said. "A lot of the times they're sick with other things, and then they get Candida auris on top of that."

A CDC fact sheet estimates that more than 1 in 3 patients with invasive C auris infection die. But Chiller said that a recent review by colleagues in Pakistan of 100 candidemia patients indicated that at least half died from the infection. In addition, some of the patients were relatively healthy. The spread of C auris into healthier populations is a scenario Chiller is hoping to prevent in US hospitals.

"We want to keep it a rare infection," he said. "I'm just concerned that if it spills over into the general realm of Candida infections, like it has in some of these other countries, then we are dealing with the potential for a highly resistant bug to really take off."

See also:

Jul 17 CIDRAP News story "CDC reports uptick in Candida auris cases"

May 19 MMWR Notes from the Field