Jul 22, 2005 (CIDRAP News) Genetic mutations in monkeypox viruses of West African origin might have spared the lives of people infected with the virus in the United States, according to a recent report.

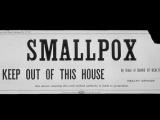

Though primarily a disease of rodents and nonhuman primates, monkeypox can occasionally spread to humans and cause a smallpox-like illness. In the summer of 2003, an outbreak of the disease occurred in six Midwestern states.

The source of the outbreak was traced to infected rodents from Ghana. Gambian rats and other imported African rodents were housed with prairie dogs, which acquired the virus and passed it along to humans when they were sold as pets. Now, a research group from St. Louis University Health Sciences Center has published a genetic study that may explain why none of the people infected that summer died. The results were published online Jul 13 in the journal Virology.

R. Mark L. Buller and colleagues first infected cynomolgus monkeys with one of two doses of either a Congo basin or West African monkeypox virus. The monkeys receiving Congo monkeypox showed signs of disease at 7 days after infection, and all of the monkeys infected at the higher dose died (none died at the lower dose). In contrast, none of the monkeys infected with West African monkeypox appeared ill or died, even at the higher dose.

Having confirmed a stark difference in virulence, the group then sequenced the genome of three West African monkeypox isolates and compared these sequences with the known genome of a single Congo basin isolate. They determined that the West African isolates were genetically distinct in important ways. Although the West African and Congo basin isolates differed at dozens of genes, the researchers identified one gene in particular thought to determine the difference in virulence.

The VACV-COP-C3L gene, which is important in helping the virus evade the bodys immune response, was present in the Congo basin isolate, but absent in the three virus isolates from West Africa. In addition, the researchers found that the gene in the Congo basin virus corresponded closely to a similar gene in the smallpox virus. Without this gene, the authors hypothesized, cells infected with the West African strains would be "more susceptible to antibody and complement lysis, which could diminish virus spread, and lead to less severe disease."

This genetic difference could explain why none of the 71 people infected with monkeypox in the United States died of their disease. The virus isolated from patients in the outbreak was determined to be of West African origin, like the less virulent isolates in the study.

The authors also propose that their findings could shed light on epidemiologic data in Africa. Previous studies have showed similar prevalence of antibodies against monkeypox among people in the Congo basin and West Africa. However, more than 90% of human cases of monkeypox, including all fatal cases, occurred in the Congo basin. The new genetic information provides an explanation for this difference in morbidity and mortality.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease and Canada's Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council.

Chen N, Li G, Liszewski MK, et al. Virulence differences between monkeypox virus isolates from West Africa and the Congo basin. Virology 2005 (published online Jul 13) [Abstract]

See also: