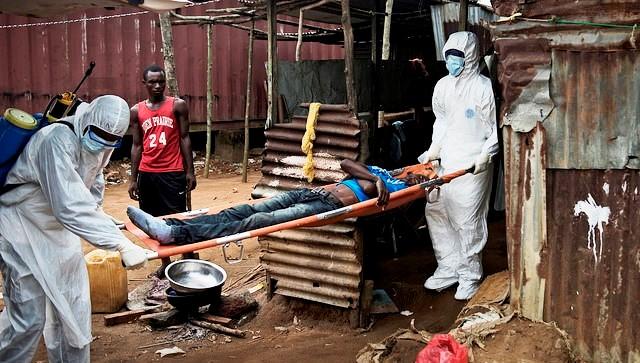

During the peak of West Africa's Ebola epidemic last year, leading public health authorities firmly proclaimed that Ebola viruses are not airborne pathogens that can spread like the viruses that cause measles or chickenpox—that they can be transmitted only through direct contact with infected bodily fluids.

Now an international team of experts is saying, in effect, "Don't be so sure." They make their argument in an "opinion/hypothesis" article published today in mBio, the journal of the American Society for Microbiology.

The authors reviewed scores of studies on human Ebola outbreaks and animal experiments, aiming to sort out what is known and not known about transmission. They concluded that, though current knowledge is very incomplete, airborne infectious particles are likely to play some role in transmission.

"It is very likely that at least some degree of Ebola virus transmission currently occurs via infectious aerosols generated from the gastrointestinal tract, the respiratory tract, or medical procedures, although this has been difficult to definitively demonstrate or rule out, since those exposed to infectious aerosols also are most likely to be in close proximity to and in direct contact with an infected case," they wrote.

In addition, they suggest that Ebola viruses have the potential to evolve in the future into pathogens that spread mainly by the respiratory route, "particularly if extensive ongoing human transmission results in selective virus evolution."

The authors include several members of the University of Minnesota's Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, publisher of CIDRAP News, as well as experts from other US academic institutions, the Public Health Agency of Canada, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sierra Leone, Doctors without Borders, and the World Health Organization (WHO).

The first author is CIDRAP Director Michael T. Osterholm, PhD, MPH, who created a stir last September when he worried in the New York Times that Ebola viruses could mutate to become transmissible through the air. He said the West African epidemic was giving the virus abundant opportunities to evolve in that direction.

The WHO was sufficiently concerned about talk of airborne Ebola transmission to respond with a pointed statement in October. The agency proclaimed that Ebola was not an airborne infection and was not likely to become one, adding that scientists did not know of any virus that had ever "dramatically changed its mode of transmission."

Some other experts contacted by CIDRAP News today said that Ebola may be able spread short distances via suspended droplets but felt that such transmission is probably rare.

Findings from human outbreaks

From studies on human Ebola outbreaks, the mBio authors conclude that direct contact and exposure to infected body fluids are the chief modes of Ebola transmission. They explain that Ebola virus has been cultured from saliva, breast milk, urine, and semen from infected patients and that viral DNA has been found in stool, tears, and sweat and in rectal, conjunctival, vaginal, and skin swabs. Further, infected persons can shed the virus for weeks to months after recovery.

Other findings and observations gleaned from Ebola outbreaks, the article says, include these:

- People exposed to Ebola patients can have asymptomatic infections, but they are not likely to pass the virus to others

- Mildly ill persons may be able to transmit the virus, but this happens infrequently if at all

- Patients in the late stages of disease, with severe diarrhea, vomiting, bleeding, or coughing, may be more likely to shed virus in aerosol particles of various sizes

- Some patients may be "super spreaders," passing the virus to many others

- The infectious dose of Ebola virus appears to be very low, perhaps 10 or fewer viral particles

As for pathology studies, the report says few autopsies have been done on Eobla victims, but so far EVD is not known to cause pneumonitis (lung inflammation) in humans. However, congestion and alveolar damage can occur.

What's known from animal studies

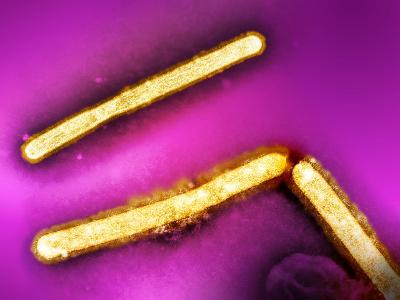

A few animal studies have suggested the possibility of Ebola transmission via aerosols, the authors found.

One study involved Ebola-inoculated rhesus monkeys and control monkeys that were housed in the same room but separated by about 3 meters. Two of the three control monkeys developed Ebola virus disease (EVD) 10 and 11 days after the death of the infected monkeys.

The researchers suggested that the controls had been infected through aerosol, oral, or conjunctival exposure to virus-laden droplets, and said studies of lung tissue suggested aerosol infection.

In another study, six infected piglets were placed near four caged macaques, with a wire barrier that kept the piglets at least 20 centimeters from the cages. All the macaques were infected. The researchers concluded that transmission could have been due to inhalation of aerosols, but other routes were also possible, such as droplets landing on objects in the cages.

In a third study, however, two uninfected monkeys did not contract Ebola after being placed next to two infected monkeys in open-barred cages for several days.

Revising an infection control paradigm

The authors' argument about Ebola as a possible respiratory pathogen hinges in part on a revision of the traditional infection control paradigm regarding pathogen transmission via particles. The traditional model, they write, holds that such transmission can happen in only two ways: large droplets making direct contact with the skin or mucus membranes, or inhalation of small airborne particles at a distance from the source.

The authors say this model fails to recognize that infectious aerosols "include suspended particles in a wide range of particle sizes (small to large droplets) that are easily inhaled by someone standing near the point of generation. Thus, aerosol inhalation can occur both near and far from an infectious source."

They further observe that vomiting caused by norovirus infection can produce infectious aerosols that lead to transmission, though norovirus is not regarded as a respiratory pathogen. Something similar, they suggest, could happen with Ebola virus, because infectious suspended particles may be generated by vomiting, diarrhea, or coughing.

In an experiment that supported this possibility, researchers created Ebola virus aerosols and assessed their decay rates. From the findings, they estimated that the Zaire species of Ebola virus can survive in aerosols for about 100 minutes.

Many questions persist

At the same time, the authors acknowledge that data on Ebola transmission are very limited, leaving the role of aerosol transmission unclear. The lack of data also dictates several other major uncertainties as well:

- The potential role of "super spreading" events is unknown.

- There is no conclusive information on the role that fomites play.

- At what point infected persons become infectious is not very clear.

- Patients can shed the virus for several months after recovery, but the epidemiologic significance of this is unknown.

- In the West African epidemic, it is not known whether wild or domestic animals are amplifying transmission.

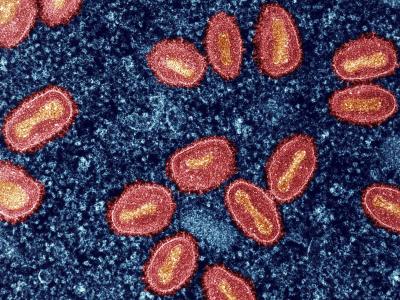

The authors grant that present evidence doesn't show Ebola to be a primary pulmonary infection with respiratory transmission, but they say it is worth asking whether this could happen in the future. They cite several lines of evidence they see as suggesting this could be possible, including that Ebola virus can be isolated from saliva and can infect several cell types found in the respiratory tract.

In conclusion, the researchers say they agree with leading public health agencies that airborne transmission of Ebola, meaning airborne spread of small particles over time and distance, is unlikely to occur because it would require genotypic changes in the virus. "However," they add, "with phenotypic changes in the virus, aerosol transmission . . . involving droplets of various sizes from cases in relatively close proximity to uninfected persons remains plausible."

Noting that the West African epidemic surprised even the best infectious disease experts, the researchers warn, "We should not assume that Ebola viruses are not capable of surprising us again at some point in the future."

Cautious reactions

The article was greeted cautiously by a virologist and an infection prevention expert who were contacted by CIDRAP News.

Vincent Munster, PhD, head of the Viral Ecology Unit at the National Institutes of Health's Rocky Mountain Laboratories in Hamilton, Mont., said Ebola transmission is probably possible via airborne droplets over very short distances, but questioned whether it is epidemiologically significant.

"If you look back at previous outbreaks and the current one, I think there is too much emphasis [in the article] on the potential for airborne transmission or aerosol transmission, as they call it," he said in an interview. He added that the authors seem to lump aerosol and droplet transmission together, whereas aerosols normally are described as small particles that can travel long distances, while respiratory droplets are large and can travel only about 1 meter.

"I think if you perform droplet-generating procedures with fluids loaded with Ebola viruses, you can get infected," Munster said. "But the question is how often does that really happen, and we don't know that too well."

In the case of an Ebola patient with diarrhea, he added, that might produce some particles in the air, "but whether that would actually lead to efficient transmission, we just don't know."

"I don't think you should exclude it, but if droplet transmission only takes place in 1 out of 1,000 cases, epidemiologically it might not be that relevant," Munster said. "But what these authors show quite nicely is that we have a very poor understanding of Ebola virus transmission, and that's what we should focus on."

Linda Dickey, RN, MPH, CIC, an infection preventionist at the University of California, Irvine, Medical Center, said she agreed that infectious droplets can probably spread Ebola over short distances, but that true airborne transmission is unlikely. She is a former member of the Practice Guidance Committee of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology.

"When somebody might have Ebola in their sputum or in their vomit, you're going to create droplets," she said. "I don't think anyone would dispute that when you have direct contact with droplets on mucus membrane, you have transmission. In a sense that's sort of like contact, it's just contact with large droplets."

But she said she doesn't believe—and the authors aren't necessarily suggesting—that Ebola is transmitted by inhalation of particles that travel longer distances.

"You'd think epidemiologically and empirically that we'd see a lot more cases in the community if it were truly spread in the air over long distances," Dickey said. "The epidemiologic evidence indicates contact spread, and droplets are certainly implicated with that, but I don't see the evidence for true airborne spread."

She observed that classifying Ebola virus as an airborne pathogen would have many implications for hospital construction, personal protective equipment (PPE), and healthcare worker training.

She noted that the guidelines for infection control when caring for Ebola patients are already causing difficulties for healthcare workers in California. "One thing we're struggling with in California is that there is insistence on having totally impermeable PPE that we've never even worked with in operating rooms or emergency departments with a lot of blood and body fluid exposure," she said.

Some of the equipment is very hot, is difficult to remove, and makes it hard to provide care for any length of time, she added.

Dickey also noted that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends wearing PAPRs (powered air-purifying respirators) when doing aerosol-generating procedures with Ebola patients.

"I don't think that is unreasonable, since PAPRs allow workers to be a lot cooler, plus it's going to protect them from droplets," she said. "But I don't see evidence and I don't believe that the requirement is indicating that there is a belief that the disease is airborne-spread and that you have to wear a PAPR to protect yourself from spread across a room, for example."

Osterholm MT, Moore KA, Kelley NS, et al. Transmission of Ebola viruses: what we know and what we do not know. mBio 2015 (early online publication Feb 19) [Abstract]

See also:

Sep 11, 2014, New York Times op-ed article by Osterholm