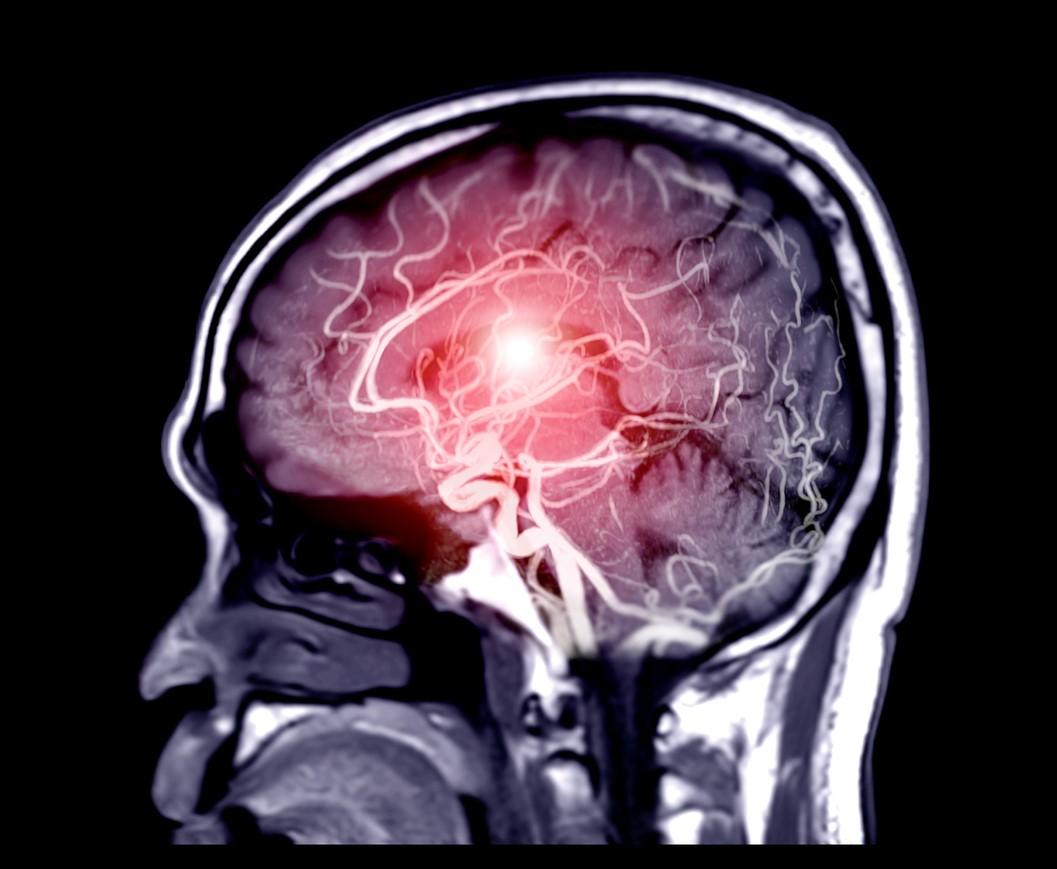

Although SARS-CoV-2 probably does not infect the brain, it can damage it significantly, a new study of autopsies of 41 COVID-19 patients finds.

Researchers at Columbia University say that they found no signs of virus inside the patients' brain cells but saw many brain abnormalities that could explain the confusion and delirium seen in some patients with severe coronavirus and the lingering "brain fog" in those with mild disease.

The study, which the authors called the largest COVID-19 brain autopsy report thus far, involved analysis of samples from autopsies conducted from March to June 2020 and was published late last week in Brain. The findings, they said, suggest that the inflammation triggered by the coronavirus in other parts of the body or in the brain's blood vessels may have caused the neurologic abnormalities seen in the autopsies.

Lack of oxygen, cell death

The brain damage consisted of areas starved of oxygen, many of them hemorrhagic, which the researchers said were likely caused by blood clots that temporarily blocked the flow of oxygen. Many activated microglia, or immune cells in the brain that can be activated by pathogens, were also identified.

"We found clusters of microglia attacking neurons, a process called 'neuronophagia,'" co-senior author Peter Canoll, MD, PhD, said in a Columbia University press release.

Because no virus was observed in the brain, he said that the microglia may have been activated by inflammatory cytokines, which are tied to coronavirus infection. "At the same time, hypoxia [reduced oxygen from COVID-19] can induce the expression of 'eat me' signals on the surface of neurons, making hypoxic neurons more vulnerable to activated microglia."

Most activated microglia were found in the lower brain stem, which is responsible for heart and breathing rhythms and levels of consciousness, and in the hippocampus, which is involved in mood and memory.

"We know the microglia activity will lead to loss of neurons, and that loss is permanent," co-senior author James Goldman, MD, PhD, said in the release. "Is there enough loss of neurons in the hippocampus to cause memory problems? Or in other parts of the brain that help direct our attention? It's possible, but we really don't know at this point."

Implications for survivors

Of the 41 patients, 59% required intensive care, and about half required intubation. Hospital-related complications were common, including deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism (20%), acute kidney injury necessitating dialysis (17%), and bacteremia (24%). About 20% of patients died within 24 hours of hospitalization, while 27% died 4 or more weeks after admission.

All of the patients, who were 74 years on average, had signs of virus-related lung damage. Sixty-six percent of the patients were men, and 83% were Hispanic/Latino.

The authors said that future studies should aim to determine whether some COVID-19 survivors have any of these neurologic abnormalities and whether they lead to chronic neurologic deficits.

"In light of the brainstem and hippocampal distribution of microglial activation, the latter of which has been linked to virus-induced cognitive deficits, it is notable that some COVID-19 survivors develop neuropsychiatric symptoms, including memory disturbances, somnolence, fatigue and insomnia, and that similar symptoms are reported in both the acute and recovery phases," they wrote.

"This study included only patients who were severely ill and died. These changes may not be seen in patients with mild illness."