A new surveillance report by Australian health officials has found rising antibiotic resistance in the most common cause of bacteremia.

Data from the Australian Group on Antimicrobial Resistance (AGAR) 2016 report on sepsis outcomes show increasing non-susceptibility in Escherichia coli to key antibiotics such as ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin. E coli accounted for 36.8% of more than 11,000 episodes of bacteremia in Australia.

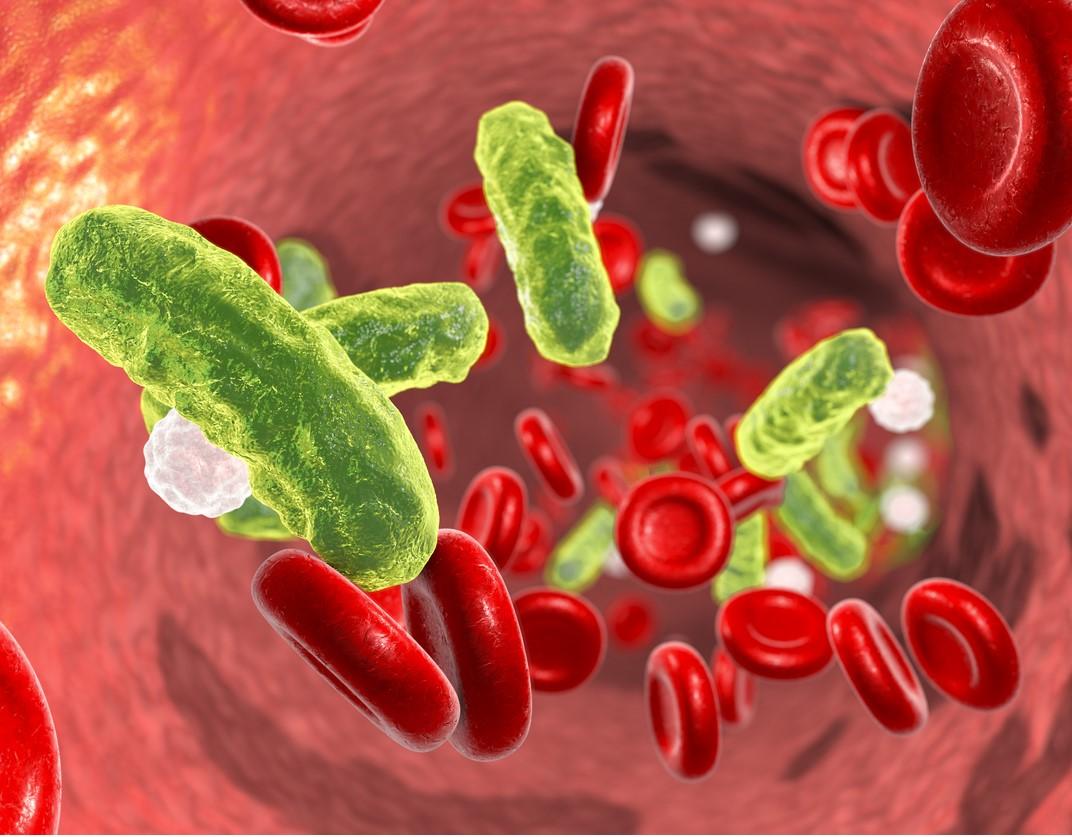

Bacteremia—the presence of bacteria in the bloodstream—can be a trigger for sepsis, a severe, life-threatening response of the immune system to bacterial infection. The report uses bacteremia as an indicator of true invasive bacterial infections. The AGAR data, which are used by Australian hospitals to make informed decisions about antibiotic therapy and care for patients with sepsis, comes from 32 healthcare institutions across Australia.

Rising resistance to fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins

Of note, 11.4% of E coli isolates causing community-onset bacteremia were ceftriaxone resistant (up from 7% in 2013), and 14% of all E coli bacteremia cases were ciprofloxacin resistant. Fluoroquinolone resistance in hospital-onset E coli bacteremia rose from 13.7% in 2013 to 20.2% in 2016.

Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) enzymes, which confer resistance to multiple classes of antibiotics—including beta-lactam antibiotics and third-generation cephalosporins such as ceftriaxone—were found in 12.7% of E coli isolates and 9.1% of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates. Additionally, more than 75% of the E coli isolates with an ESBL phenotype harbored CTX-M genes, a type of ESBL carried on plasmids (mobile pieces of DNA) that frequently contain fluoroquinolone and other resistance genes.

Rising fluoroquinolone resistance in E coli in Australia has been linked to the worldwide spread of E coli ST131, an epidemic lineage of E coli associated with resistance to fluoroquinolones and third-generation cephalosporins. The authors of the report also suggest that because fluoroquinolone resistance is often linked to cephalosporin resistance caused by the CTX-M type, it's possible that high use of oral cephalosporins and penicillins in the community is driving this resistance.

The findings are concerning, the authors note, because fluoroquinolones are relied on as important "rear-guard" oral antibiotics that are used for step-down treatment in invasive infections or when an infection is resistant to other gram-negative oral antibiotics. Australia has tried to restrict unnecessary fluoroquinolone use in human and veterinary medicine.

Rising resistance to third-generation cephalosporins is also troubling, because current Australian guidelines recommend the drugs for empiric treatment of severe gram-negative infections, partly to avoid broader-spectrum antibiotics. According to the report, the most frequent origin of gram-negative bacteremia was urinary tract infections.

In addition, the authors note that while ESBLs were initially more common in hospital-associated infections, they are increasingly becoming a community problem. An estimated 83% of E coli bacteremia episodes in 2016 were community-onset.

"This indicates that a substantial reservoir of resistance exists in the community, particularly in the elderly population and in long-term residential care settings," the authors write. "If the rate continues to rise, it will potentially affect the application of therapeutic guidelines such as guidelines for empirical treatment of severe infections."

Data on gram-negative bacteremia also showed that rates of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) were found to be low—less than 0.1% in E coli and 0.3% in K pneumoniae. Two E coli isolates carrying the MCR-1 colistin-resistance gene were identified, but those isolates did not contain ESBLs or carbapenemase enzymes.

Other causes of bacteremia

The report also addressed antibiotic resistance in two other common bacterial causes of bloodstream infections, enterococci and Staphylococcus aureus.

Among the key findings were that ampicillin resistance and multidrug resistance, including resistance to gentamicin and vancomycin, are common in Enterococcus faecium. The report notes that the percentage of E faecium bacteremia isolates resistant to vancomycin in Australia (46.5%) is now much higher than in almost all European countries, and that the use of vancomycin for treating E faecium bacteremia can no longer be recommended.

E faecium and Enterococcus faecalis are the two leading causes enterococcal bacteremia, accounting for 1,058 episodes in 2016. But of the two, E faecium has a considerably higher all-cause 30-day mortality rate—27.1% compared with 12.9% for E faecalis. The report suggests the limited treatment options for E faecium may be a factor.

Of the 2,580 bacteremia episodes caused by S aureus, 19.7% were found to be caused by methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA), up from 18.6% in 2015. In addition, the report notes that MRSA is rising among both hospital-onset and community-onset cases of S aureus bacteremia. The fact that more than three quarters of the S aureus bacteremia episodes were community-onset points to the rapidly changing nature of MRSA in Australia, according to the authors.

See also:

Feb 28 AGAR 2016 sepsis outcomes report