A decolonization program implemented at a network of healthcare facilities in southern California significantly reduced the prevalence of multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) on patients' skin, researchers reported yesterday in JAMA.

But the overall impact of the intervention went beyond reduced MDRO colonization. The regional collaboration, in which more than 50,000 patients at 16 hospitals, 16 nursing homes, and 3 long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs) were routinely bathed with an antiseptic soap and given an antiseptic nasal ointment, also resulted in reduced infections, hospitalizations, hospitalization-related costs, and deaths.

The authors of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-funded study estimate that over the 25 months of the intervention, the decolonization strategy prevented 800 hospitalizations and 60 deaths.

Corresponding author Susan Huang, MD, MPH, of the University of California Irvine School of Medicine, said that while she and her colleagues hoped that the intervention would reduce MDRO colonization, they were excited to see the cascade of effects in a network of facilities that frequently share patients and the difficult-to-treat drug-resistant bacteria that they carry with them.

"What we're so pleased about is not only were we able to show that the amount of people who have [MDROs] on their bodies in the hospital, in the nursing home, and in the LTACHs substantially went down, but then we could actually translate that at every stage," Huang told CIDRAP News.

Routine bathing, nasal decolonization

The intervention was the second stage of a CDC-funded two-part public health endeavor called SHIELD-OC (the Shared Healthcare Intervention to Eliminate Life-Threatening Dissemination of MDROs in Orange County), which aimed to identify a high-yield strategy for reducing MDROs and the complications they can cause in a network of hospitals, nursing homes, and LTACHs in the nation's sixth-largest county. While the prevalence of MDROs is roughly 10% to 15% in hospitals, research has shown that it's as high as 65% in nursing homes and 80% in LTACHs.

In the first part, a simulation model identified decolonization as the most effective strategy. Huang and her colleagues then did a networking analysis to find the hospitals, nursing homes, and LTACHs that share the most patients. Coordination among these facilities is crucial, Huang explained, because the pathogens don't remain within the walls of a single facility. Rather, the frequent movement of MDRO-colonized patients between facilities fuels the spread of resistant pathogens that can infect other patients.

"Bacteria sit happily on your body for weeks, months, years," Huang said. "And because of that, when you then go to this hospital or that nursing home, these things can spread because they're still on your body and then you shed them."

Colonization also poses a risk to the patients themselves, who could become infected if they have to undergo surgery or have a medical device inserted.

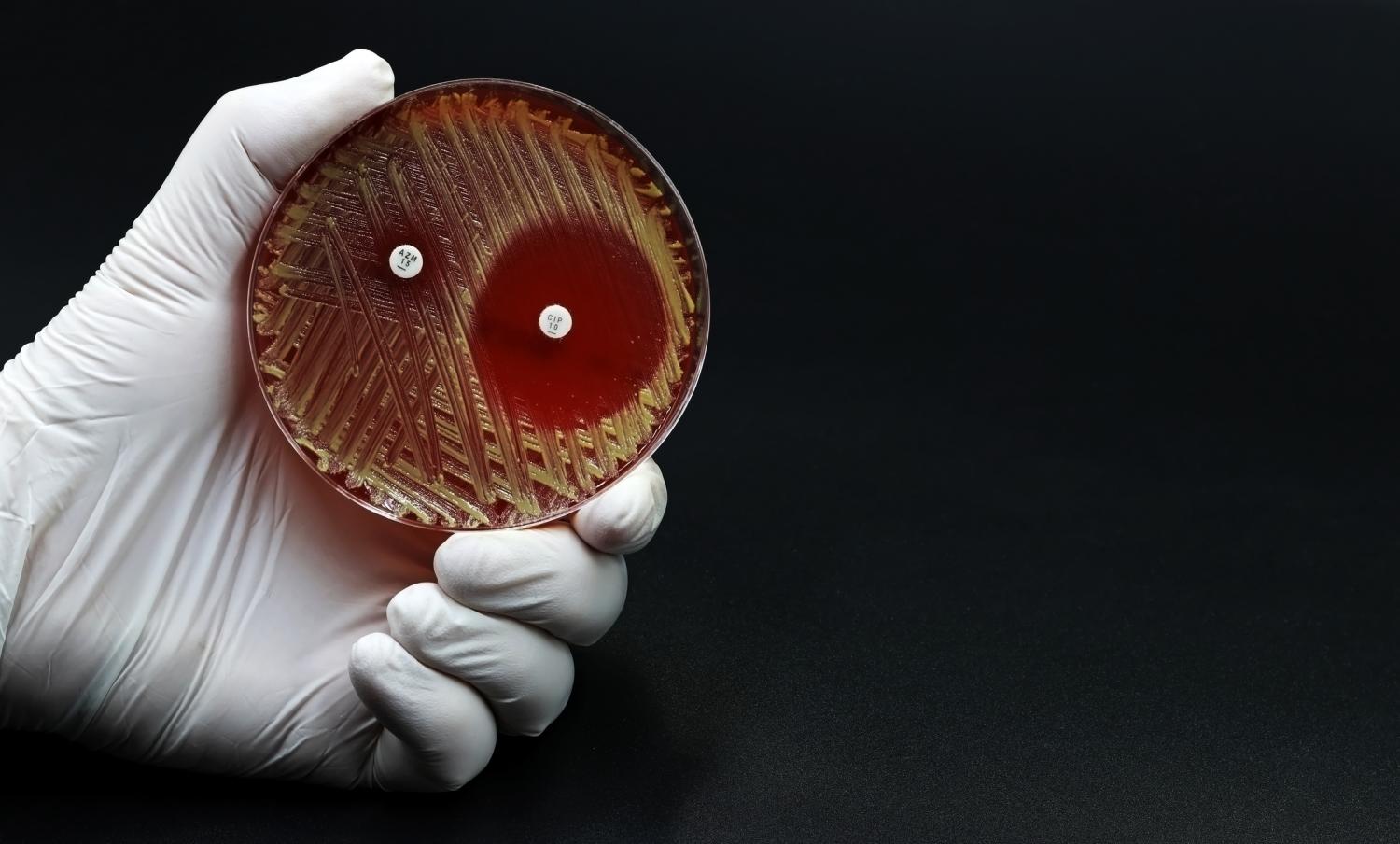

Over the 25-month intervention period (July 2017 through July 2019), 35 facilities implemented the decolonization strategy. At the nursing homes and LTACHs, the strategy was implemented universally—all patients were routinely bathed with a chlorhexidine-containing product and received twice-daily nasal iodophor for 5 days, every other week. The participating hospitals targeted patients under contact precautions.

Using these products to decolonize patients isn't a new strategy. Both products have been shown to reduce colonization with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and are widely used in healthcare facilities to protect patients from infections, particularly those in intensive care units. Subsequent research has found that chlorhexidine is also effective against several resistant pathogens that can cause healthcare-associated infections, such as vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)–producing bacteria.

"It works against gram-positive and gram-negative pathogens, and it accounts for the vast majority of resistant organisms that the CDC and others are worried about," Huang said.

Biggest impact seen in nursing homes, LTACHs

To evaluate the impact of the intervention, the researchers assessed MDRO carriage prevalence in all participating facilities at the end of the intervention compared with a baseline period (February 2015 through February 2017). Additional outcomes included incident MDRO clinical cultures (i.e., cultures sent to the lab to identify an infection) in participating versus non-participating facilities, and infection-related hospitalizations, associated costs, and deaths among residents in participating versus nonparticipating nursing homes.

The biggest impact on MDRO colonization was seen in the nursing homes and LTACHs, where MDRO prevalence fell from 63.9% to 49.9% (a 21.9% relative decrease) and 80% to 53.3% (a 33% relative decrease), respectively. In hospitalized patients, MDRO prevalence fell 64.1% to 55.4% (a 13.6% relative decrease). Adjusted analyses showed significant declines in the prevalence of MRSA, VRE, and ESBL–producing bacteria, while hospitals saw significant declines in VRE and ESBLs.

What we're so pleased about is not only were we able to show that the amount of people who have [MDROs] on their bodies in the hospital, in the nursing home, and in the LTACHs substantially went down, but then we could actually translate that at every stage.

The effect on incident MDRO clinical cultures was similar. In adjusted models, there was a 30.4% reduction in MDRO-positive clinical cultures at participating nursing homes compared with nonparticipating nursing homes, while LTACHs (all of which participated) saw a 22.5% reduction. Compared with nonparticipating hospitals, the hospitals that implemented the decolonization strategy saw a 12.9% reduction in MDRO-positive clinical cultures.

In participating nursing homes, the rate of infection-related hospitalizations per 1,000 resident-days fell 26.7%, associated hospitalization costs fell 26.8%, and deaths from infection-related hospitalizations declined 23.7% compared with nonparticipating nursing homes.

"I think it's really exciting to see something that can tell the full story from what's on the body all the way through hospitalization and deaths," Huang said.

The value of coordination

CDC officials say the findings provide further evidence that efforts to fight the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria should start at the regional level, among patient-sharing networks.

"Preventing the spread of resistant germs in one healthcare facility can protect patients and residents at that facility, but also at facilities receiving patients via transfer, resulting in synergy across the regional healthcare network," Kara Jacobs-Slifka, MD, lead for long-term care at the CDC, said in a UC Irvine Health press release.

In an accompanying editorial, Christopher Crnich, MD, PhD, of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, points out that this kind of collaborative effort is important because hospitals engaged in aggressive MDRO containment efforts may still see rising MDRO incidence if the other facilities in their patient network don't make the same effort. In addition, he notes that long-term care facilities (LTCFs) that provide high volumes of postacute care have been repeatedly implicated in regional MDRO outbreaks.

"The study…highlights the value of coordinating MDRO control efforts across a given patient-sharing network and particularly the benefit of centering these efforts on LTCFs [long-term care facilities]," Crnich writes.

For Huang, the findings are additionally significant given that the emergence and spread of MDROs is outpacing the development of new antibiotics.

"Prevention is becoming mission critical because therapies are limited," she said. "The infections will never go away as much as we wish they would, but we can certainly do everything we can to get them to the lowest possible level."