Aug 29, 2005 (CIDRAP News) Scientists in Texas report they have found a way to detect abnormal prion protein in blood, an achievement that could lead to the first practical blood test for bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) and similar diseases in living animals.

The test was used successfully to detect a prion disease in hamsters. If it proves effective in cattle and humans, it could help protect the blood supply from BSE, help determine the prevalence of the disease in US cattle, and assist researchers trying to assess how many people are unwittingly infected with variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD), the human equivalent of BSE.

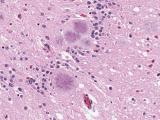

At present, BSE and related prion diseases, called transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), can be definitively diagnosed only by examination of brain tissue after death. In the United Kingdom, BSE spread through cattle herds in the 1980s and early 1990s and led to more than 150 cases of vCJD in people, presumably as a result of eating beef from infected animals. The United States has had two BSE cases so far.

Because TSEs take years to produce symptoms, it is feared that many more Britons were infected unknowingly and will fall ill in the years ahead. The discovery in Britain of a few possible cases of transmission of vCJD through blood transfusions has fueled more concern.

The new blood test was developed by Claudio Soto and two colleagues at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston (UTMB). Writing in Nature Medicne, they report that they devised a way to stimulate a tiny, undetectable amount of abnormal prion protein in a blood sample to multiply so that it reaches detectable levels.

"Our findings represent the first time that prions have been biochemically detected in blood," the authors state. Because the test appears to be highly accurate, it "offers promise for the design of a sensitive biochemical test for blood diagnosis of transmissible spongiform encephalopathies."

The method is called protein misfolding cyclic amplification (PMCA). It involves separating the "buffy coat" portion of a blood sample, adding a dose of normal prion protein from brain tissue to it, incubating the preparation at 37˚C, exposing it to sound waves, and repeating the process many times. If abnormal prion protein is present, it causes the normal prions to convert to the abnormal, misfolded form, forming small clumps, the report says. The sonic treatment breaks up the clumps into smaller bits, stimulating further conversion as the cycle is repeated. After a number of rounds of PMCA, the abnormal protein can be detected by an existing test, such as the Western blot.

The authors described the basic process in previous reports, and in the new article they write that they found a way to automate the process to speed it up and increase the number of cycles.

To evaluate the test, they used 12 healthy hamsters and 18 hamsters that had clinical signs of scrapie (the sheep form of TSE) after being inoculated with infected brain tissue. After six rounds of PMCA, abnormal prion protein was detected in blood samples from 16 of the 18 sick hamsters, but not in any of the samples from healthy hamsters. The findings signify 89% sensitivity and 100% specificity for the test.

In its current form, PMCA testing takes several days to yield a highly sensitive result, the report says. The authors say they expect to further increase the speed of the test.

The researchers predict that the development of a similar blood test for humans will have a "tremendous impact" on the beef industry, the safety of blood and blood products, and estimation of the number of vCJD cases. They suggest that the test could permit the diagnosis and treatment of vCJD early in its course, before the appearance of clinical signs and permanent brain damage. The disease is currently untreatable and always fatal.

In a UTMB news release, Soto commented, "The next step, which we're currently working on, will be detecting prions in the blood of animals before they develop clinical symptoms and applying the technology to human blood samples."

According to an Associated Press report, Soto also said he hopes to evaluate the test in animals that have been naturally infected with a TSE and in animals that have asymptomatic infections.

Castilla J, Saa P, Soto C. Detection of prions in blood. Nature Medicine 2005; early online release [Abstract]

http://www.nature.com/nm/journal/v11/n9/abs/nm1286.html