Jul 9, 2004 (CIDRAP News) The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) said today it is banning cattle parts that could contain the bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) agent from food supplements and cosmetics, but it is not yet ready to ban those parts from all feed for animals, including pets.

The FDA had announced plans in January to ban high-risk cattle tissues, or "specified risk materials" (SRMs), from food, food supplements, and cosmetics. But the agency never officially imposed the ban. Officials said today it would take effect Jul 14, when it will be published in the Federal Register.

The US Department of Agriculture (USDA), which regulates meat, poultry, and eggs, banned SRMs from those foods in January, following the discovery of a BSE case in Washington state in December. The FDA regulates all other foods, as well as supplements and cosmetics.

The FDA said today it has reached a "preliminary" decision to ban SRMs from all animal feed, but it wants to gather public comments before going ahead. In a telephone briefing, officials said the agency would take comments for 60 to 120 days.

"FDA has reached a preliminary conclusion that it should propose to remove SRM's from all animal feed and is currently working on a proposal to accomplish this goal," the agency said in a news release. The agency is issuing an "advance notice of proposed rulemaking" on the topic.

Cattle contract BSE, or mad cow disease, by eating feed containing protein from other infected cattle. To prevent the spread of BSE, the FDA in 1997 banned the practice of putting cattle-derived protein in feed for cattle and other ruminant animals. However, cattle tissues are still used in feed for pigs, chickens, and pets.

The aim of the new proposed rule is to prevent cross-contamination, whereby SRMs in cattle parts used in feed for pigs, chickens, or pets could end up in cattle feed if both kinds of feed are made with the same equipment or in the same plant. Cross-contamination also can occur if cattle are given feed intended for other animals.

The FDA's notice of proposed rulemaking also calls for public comments on other possible actions to block pathways by which material from BSE-infected cattle could get into cattle feed. These actions include:

- Requiring that equipment for handling and storing feed be dedicated to just one kind of feed (for either ruminants or nonruminants)

- Banning the use of all mammalian and poultry protein in ruminant feed

- Banning the feeding of mammalian blood to calves

- Prohibiting the use of poultry litter (which includes bedding, spilled feed, and waste) and restaurant leftovers in cattle feed

- Banning the use of nonambulatory ("downer") cattle and cattle that die on farms in any animal feed

In its announcement in January, the FDA had described plans to ban the feeding of mammalian blood to calves, halt the use of poultry litter and restaurant leftovers in cattle feed, and require "dedicated equipment" in feed handling and storage. But the agency never followed through on those restrictions at the time.

Today the FDA said that banning SRMs from all animal feed could render unnecessary some of the other possible steps for reducing feed-related risks. Such a ban was a key recommendation from an international team of experts that reviewed the USDA's actions on BSE early this year, FDA officials said.

The international review team (IRT) released its report about a week after the FDA's January announcement. The team said the single most important measure for reducing feed-related BSE risks was to eliminate SRMs from all animal feed, Steve Sundlof of the FDA's Center for Veterinary Medicine said today.

"The IRT approach is to prevent potentially infective tissues from ever entering animal feed channels," the FDA's notice of proposed rulemaking says. "Although FDA believes the measures previously announced would serve to reduce the already small risk of BSE spread through animal feed, the broader measures recommended by the IRT, if implemented, could make some of the previously announced measures unnecessary."

However, "either approach would require a significant change in current feed manufacturing practices," the notice states. "Therefore, the FDA believes that additional information is needed to determine the best course of action."

Sundlof said there is concern that banning poultry litter from cattle feed would cause disposal problems. The litter would have to be disposed of on land, which might mean it would end up on cattle pastures, he said.

In response to questions, Sundlof said he couldn't specify the amount of SRMs that are currently used in animal feed, but he said that dealing with them would be "a complicated issue" if they were banned. "It would most likely require that the rendering industry at least partially restructure to include a sector that is for disposal only," he said.

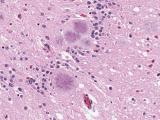

SRMs, as defined by USDA and FDA, include the brain, skull, eyes, trigeminal ganglia, spinal cord, vertebral column, and dorsal root ganglia of cattle aged 30 months or older, plus the tonsils and small intestine of all cattle. In BSE-infected cattle, these are the tissues most likely to contain infectious prion protein.

In addition to SRMs, certain other cattle materials will be banned from foods, supplements, and cosmetics, the FDA said. These include material from downer cattle and cattle not inspected and approved for human consumption, plus mechanically separated beef.

FDA officials today said the percentage of food supplements and cosmetics that contain SRMs is very small, but they couldn't give a specific number.

See also:

Jan 26, 2004, news release on BSE-related rules planned by FDA at that time

http://archive.hhs.gov/news/press/2004pres/20040126.html