Webster RG, Govorkova EA. H5N1 influenza--continuing evolution and spread. (Perspective) N Engl J Med 2006 Nov 23;355(21):2174-7 [Full text]

(CIDRAP Source Weekly Briefing) – Certain recent new stories may have sown confusion about whether the threat of pandemic influenza still exists, and whether the world needs to continue to prepare. A New England Journal of Medicine article published last week provides the antidote, and the answer: It does, and we do.

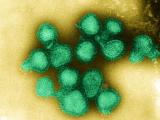

Reknowned avian flu expert Robert G. Webster, PhD, and colleague Elena Govorkova, MD, PhD, enumerate several factors that support the conclusion that the situation is worsening, not abating.

These factors include an increasing number of countries affected [add link to graphic], ever increasing genetic differences within H5N1 "clades" (subgroups of the deadly form of avian flu virus), antiviral drug resistance, lack of adequate disease control in developing countries, imperfect poultry vaccinations, and continued infection in waterfowl.

Webster and Govorkova point out that H5N1 originated in Southeast Asia, similar to the origin of the last two pandemics in 1957 and 1968.

The authors also explain how the H5N1 virus has emerged into two clades (clades 1 and 2) or genetically distinct viruses, the latter of which is further divided into three subclades. Unfortunately, these H5N1 categories differ enough genetically that a vaccine against one is unlikely to provide protection against the others.

The authors do suggest that protection offered by a vaccine against one clade may offer some benefit against death if the pandemic is caused by other clades or subclades. Thus, they believe that it is "worth stockpiling" pre-pandemic vaccines, which differs from recent advice from the World Health Organization (WHO).

Another obstacle to stopping the spread of avian influenza has been resistance to antivirals such as oseltamivir (Tamiflu). The authors point out that most of the clade 1 viruses are resistant, while most clade 2 viruses are not. Adding to the problem has been a delay in administering antivirals to patients with H5N1 infection in many instances, which may further promote natural selection of resistant strains because of high levels of virus in the patient's body.

The article also points out that, although controlling H5N1 influenza through culling and quarantining domestic poultry has worked for some wealthy countries such as Japan, that hasn't been the case in poorer countries such as Thailand. Of note, in the past week, (The authors also mention South Korea's success, but just within the past week it reported two separate H5N1 outbreaks in domestic poultry, calling into question the long-term effectiveness of Korea's approach.)

In addition, the authors do note that the effort to vaccinate uninfected poultry in conjunction with quarantine and culling by China, Indonesia, and Vietnam has failed, because the poultry vaccines are of poor quality, do not provide sufficient immunity, and promote genetic changes in the virus that may aid its spread.

Webster and Govorkova point out that since Vietnam adopted a strategy of vaccinating all poultry with an inactivated (dead-virus), oil-emulsion H5N1 vaccine, there have been no additional cases in humans and no reported H5N1 infections in chickens.

But in September 2006, H5N1 was reported to have emerged in ducks and geese in Vietnam, the report says.

"Thus, H5N1 influenza vaccine seems to protect chickens, and indirectly, humans, but probably not waterfowl," the writers state. The pair hypothesize that this could be the reason why H5N1 is not under control in China.

"Clearly we must prepare for the possibility of an influenza pandemic," the article concludes. "If H5N1 influenza achieves pandemic status in humans—and we have no way to know whether it will—the results could be catastrophic."

Comments from the Editor-in-Chief:

Over recent months the No. 1 question that I am asked by many in the media and the general public goes something like this: "So, we don't have to worry about that bird flu scare anymore . . . do we?" This perspective article by Webster and Govorkova should be required reading for each one of these questioners. It very clearly details why we should be even more concerned about the possibility of H5N1 causing the next pandemic than we were several years ago. It is a straightforward, balanced assessment of the current situation and is written so that every CEO can understand the message.