In late March, an ominous report from England's public health agency described a case of gonorrhea that was resistant to both components of the dual antibiotic therapy of azithromycin and ceftriaxone—the only remaining recommended treatment for gonorrhea.

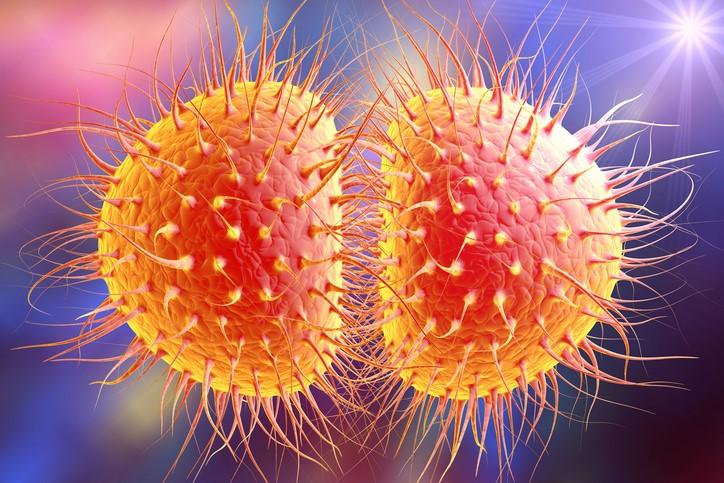

The infection, which was also resistant to a slew of other antibiotics, was quickly dubbed "super gonorrhea" by the UK press. It was the first reported case in the world of gonorrhea with combined high-level azithromycin resistance and ceftriaxone resistance.

It certainly won't be the last. In the following months, two similar cases would be reported in Australia.

Ultimately, the British man's infection was cured. But not until the patient had received 3 days of intravenous (IV) treatment with ertapenem, a "last-resort" antibiotic normally reserved for severe, life-threatening infections and not intended for garden-variety sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).

"If this was to become the norm, the impact on healthcare services would be huge," Mark Lawton, MD, of the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV, told CIDRAP News.

Welcome to the world of super-resistant gonorrhea.

A history of resistance

When conversations with experts in infectious disease and antibiotic resistance come around to the topic of antibiotic-resistant gonorrhea, a common refrain eventually emerges.

It's not a matter of if gonorrhea will become resistant to the currently recommended antibiotic treatment, but when.

And that's where the certainty ends. Because after that happens, a disease that effects 78 million people globally—and has mostly been an unpleasant nuisance since the discovery of antibiotics—will no longer have any known effective antibiotics to treat it. As was seen in the UK case, clinicians may have some weapons in their arsenal for treatment of individual cases, but those options aren't ideal, nor have they been extensively studied. And new antibiotics for gonorrhea are, at best, still a few years away.

"At this point in time, with the data that we have available to us, there just isn't anything else out there that's ready to go," said Sancta St. Cyr, MD, a medical officer in the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC's) Division of STD Prevention.

That means more people left with an infection they can't shake, one that, while not life-threatening, can cause significant health problems if not properly treated. What's more, it could mark the beginning of the post-antibiotic era of medicine.

In the 80 years that clinicians have been treating the Neisseria gonorrhoeae bacterium with antibiotics, gonorrhea has proven to be a tricky foe, developing resistance to each new antibiotic within the span of a few years. Sulfonamides, discovered in 1935, were the first antimicrobial treatment for gonorrhea. When resistance to sulfonamides started to develop in the early 1940s, the "wonder drug" penicillin became the predominant treatment, curing 95% of cases. But as early as 1946, high-level resistance to penicillin was noted, and widespread treatment failure was being reported by the 1960s.

Each successive treatment—tetracycline, spectinomycin, fluoroquinolones, macrolides, and cephalosporins—has suffered a similar fate: initial success and several years of efficacy, followed by steadily increasing resistance.

"I think the process of the development of antimicrobial resistance on the part of Neisseria gonorrhoeae is an inexorable process," said Edward Hook, MD, an expert in STDs and professor at the University of Alabama-Birmingham Medical School. "That ongoing progression has now been combined with a lack of alternatives."

One of the explanations for this "inexorable process" is gonorrhea's unique capacity for acquiring resistance genes and mutations that enable it to survive and adapt to each new threat thrown its way. But gonorrhea has an additional trick up its sleeve. As St. Cyr explains, while other types of bacteria will shed resistance genes once antibiotic selection pressure has been removed, gonorrhea collects and holds on to those resistance mechanisms.

"Gonorrhea is actually gathering these mutated genes and keeping us from using drugs that have been used previously to treat the infection," she said.

Currently, the cephalosporins ceftriaxone and cefixime are the end of the line. In the United States, the dual therapy approach was adopted in 2010, with the CDC adding azithromycin to the regimen to shield ceftriaxone from resistance and to ensure that patients would receive effective treatment. The United Kingdom and other countries have also used this strategy. Most guidelines now recommend ceftriaxone over cefixime because of rising resistance to cefixime.

While this regimen has worked well so far, the expiration date on dual therapy appears to be nearing as resistance to azithromycin rises. In preliminary data released last week, the CDC reported that the proportion of azithromycin-resistant isolates in gonorrheal lab specimens rose from 1% in 2013 to more than 4% in 2017. Historically, St. Cyr said, the CDC has switched to another drug once the 5% threshold was met.

England has been seeing a similar rise in azithromycin resistance, highlighted by an outbreak of a strain of highly azithromycin-resistant gonorrhea that started in Leeds in 2015 and has spread to other parts of the country. And as Mark Lawton notes, rising resistance to azithromycin puts more pressure on ceftriaxone.

"We were aware that the increase in resistance to azithromycin we have seen in recent years would ultimately lead to reliance on the ceftriaxone component, which would then, in turn, develop resistance," Lawton said. "This is what we've seen in this recent case of 'super' gonorrhea."

The problem extends far beyond England and the United States. According to the most recent report from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 7.5% of N gonorrhoeae isolates tested in Europe were resistant to azithromycin in 2016, up from 7.2% in 2015. Data from the World Health Organization's Global Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Programme (WHO GASP) show that 62 countries have reported resistance to azithromycin and 55 have found resistance or decreased susceptibility to cefixime or ceftriaxone.

When the WHO released those data in 2017, agency officials warned that the extent of the problem was likely much greater, since most of the data were from high-income countries with good surveillance systems. Teodora Wi, MD, a medical officer with the WHO's Department of Reproductive Health and Research, told reporters there were probably cases of treatment-resistant gonorrhea in low-income countries with high STD rates, but that they haven't been documented.

And in an age where global travel is easier than ever, antibiotic resistance quickly spreads beyond national borders.

"Nowadays, there's so much international travel, there's so much commerce, and so many people going to different places and unfortunately not protecting themselves and not preventing acquisition of infection," St. Cyr said. "When you see it one place, it's generally a matter of time before it can spread to others."

"I think this is a huge global public health problem," said Hook.

While no cases of "super" gonorrhea have been reported in the United States, a cluster of cases that were highly resistant to azithromycin were reported in Hawaii in 2016. St. Cyr said the CDC, which has boosted gonorrhea surveillance capacity in recent years, is on the lookout. "We know it's just a matter of time before it comes to us," she said.

Rising STD rates

The arrival of the inevitable is also being hastened by rising rates of gonorrhea and other STDs.

The CDC's recently reported data show that the number of gonorrhea cases rose by 67% from 2013 through 2017, from 333,004 to 555,608 diagnosed cases. The United Kingdom saw a 22% increase from 2016 to 2017. And those are only the diagnosed cases. Experts suggest the true number of infections is likely higher.

The uncomfortable reality behind the rise in STDs is that, after the years of messaging about condom use and safer sex practices that proliferated in the era of HIV/AIDS, more people are engaging in unprotected sex, with a variety of partners. And gonorrhea doesn't seem to be on their radar.

"We've seen a reduction in condom use over the last few years, and that does put individuals at increased risk for all STDs, especially gonorrhea," said Stephanie Arnold-Pang, policy and government relations director for the National Coalition of STD Directors (NCSD). "People tend to think of STDs, particularly syphilis and gonorrhea, as something that happened in the 1940s and 1950s, and they don't realize that they're on the rise and that young people in particular are at risk."

Another factor is that federal and state funding for STD prevention programs has been cut in recent years, with NCSD estimating that STD programs are working on budgets that are effectively what they were 15 years ago. "Unfortunately, [scientists] don't really have enough time and resources to track down all the various diseases, especially gonorrhea, the way that we really need to to stop the spread of the disease," Arnold-Pang said.

This not only means less money for STD awareness and education, but also less money for screening and testing. If sexually active people with undiagnosed gonorrhea are having unprotected sex with multiple partners before they become aware of the symptoms or get tested, the infection can easily, and unknowingly, be spread.

Further complicating the issue is the fact that gonorrhea doesn't always produce symptoms. Urethral gonorrhea infections in men can be "horribly symptomatic and very distressing," said STD expert and University of Hawaii public health professor Alan Katz, MD, MPH, resulting in a burning sensation when urinating and green, yellow, or white discharge from the penis. "Most male patients who have urethral gonorrhea come in pretty rapidly."

Urethral gonorrhea symptoms in wome n tend to be milder, or don't appear at all. And pharyngeal gonorrhea infections, which can spread through oral sex, are frequently asymptomatic and harder to detect, as are rectal infections. While most STD clinics use nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) to assay urine for gonorrheal DNA, there is currently no Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved NAAT to test for pharyngeal or rectal gonorrhea, even though NAATs are the quickest and most accurate method of gonorrhea detection.

n tend to be milder, or don't appear at all. And pharyngeal gonorrhea infections, which can spread through oral sex, are frequently asymptomatic and harder to detect, as are rectal infections. While most STD clinics use nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) to assay urine for gonorrheal DNA, there is currently no Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved NAAT to test for pharyngeal or rectal gonorrhea, even though NAATs are the quickest and most accurate method of gonorrhea detection.

"There's no question that NAATs are extremely important for gonorrhea detection, especially from the extra-genital sites," Katz said. "They should be done on people who are exposed at those sites."

But many STD clinics and physicians aren't routinely testing these extra-genital sites, except in patients with known risk factors—such as men who have sex with men. "Most clinicians do not do a very good job of looking for extra-genital infections in heterosexual men and women," said Hook.

That means many pharyngeal gonorrhea infections could be flying under the radar.

"I think because people often don't know they have gonorrhea, silent carriage is really an issue," said Katz.

Throat as a reservoir for resistance

STD experts and public health officials are particularly concerned about pharyngeal gonorrhea, not only because it's easily transmittable and could be spreading silently, but also because it doesn't always respond to the recommended treatment regimen. "Pharyngeal cases of gonorrhea tend to be a little harder to treat, meaning that sometimes people can show signs that they've had their infections cleared at other sites, but still have signs of gonorrhea in their throat after treatment," St. Cyr explained.

That's what happened in the UK case, where the patient's urethral gonorrhea infection was cured with the initial treatment, but a pharyngeal swab taken at a follow-up visit came back positive, indicating the infection was still present in his throat. That's when the doctors turned to IV ertapenem.

The difficulty in treating pharyngeal gonorrhea could be linked to its location. Gonococcal bacteria in the throat, the hypothesis goes, can build up resistance through exposure to antibiotics being taken for other types of infections. "It's important to realize that, for the most part, the drugs that are used to treat gonorrhea are also used to treat lots of other problems," said Hook.

So when a common antibiotic like azithromycin is taken for an ear infection, for instance, it might select for resistant gonorrhea strains. On top of that, gonococcal bacteria in the throat can also add to its arsenal of defenses by acquiring mobile resistance genes from its bacterial neighbors.

This adds another layer of complexity to screening and testing, because while NAATs are the preferred method of detecting a gonorrhea infection, they can't test for antibiotic resistance. That's why the CDC is recommending that state and local health department laboratories develop the capacity to perform gonorrhea cultures: Growing N gonorrhoeae in a petri dish is currently the only way to identify drug-resistant strains and make sure patients are getting treated properly.

Katz, who was involved in the detection and treatment of the seven Hawaiian patients who had highly azithromycin-resistant gonorrhea in 2016, thinks diagnosed patients should be getting culture tests before they receive their treatment. "Screen people with the NAATs, and if they turn out positive, do a culture before you treat them," he said.

Katz noted that Hawaii been particularly focused on this type of culture-based surveillance, given that antibiotic resistant gonorrhea has historically spread east to the US from Asia, with Hawaii as one of its first stopping points. "It's always a surprise when it occurs, but we're really focused on the issue of drug-resistance, and we've put a lot of resources into being able to do good surveillance and be on top of things," he said.

Buying time until new drugs arrive

While a few promising new antibiotics are on the horizon, they likely won't be a treatment option for several more years.

One of the new drugs, solithromycin, has completed phase 3 clinical trials, the last hurdle a new drug has to complete before a pharmaceutical company can apply for FDA approval. A phase 2 study showed that a single dose of oral solithromycin resulted in 100% microbiological eradication in men and women who had uncomplicated urogenital gonorrhea.

Two other news drugs, zoliflodacin and gepotidacin, also showed promising results in phase 2 trials, and phase 3 trials are being planned for both drugs. The Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (GARDP) has entered into a partnership with biotech company Entasis Therapeutics to accelerate the development of zoliflodacin by helping register and conduct the phase 3 trial, which will be undertaken in the United States and other countries.

One of these drugs may turn out to be at least a partial answer. If not, increasing resistance to the current treatment could result in a rise in the type of complications associated with gonorrhea infections. These complications, which predominantly affect women, include infertility, pelvic inflammatory disease, and ectopic pregnancy.

Pregnant women with gonorrhea can also pass the infection on their babies. In addition, gonorrhea has been associated with an increased risk for HIV acquisition.

In developed nations like the United States and the United Kingdom, we could see increasing reliance on more powerful antibiotics like ertapenem, which could in turn hamper the ability to use those drugs for more serious multidrug-resistant bacterial infections. Poorer nations, on the other hand, might have to rely on drugs like ciprofloxacin, which is no longer recommended for gonorrhea treatment because of resistance but is still being used in many countries.

In developed nations like the United States and the United Kingdom, we could see increasing reliance on more powerful antibiotics like ertapenem, which could in turn hamper the ability to use those drugs for more serious multidrug-resistant bacterial infections. Poorer nations, on the other hand, might have to rely on drugs like ciprofloxacin, which is no longer recommended for gonorrhea treatment because of resistance but is still being used in many countries.

Neither of these options is very good. "The situation is, actually, fairly grim," GARDP director Manica Balasegaram told reporters at a WHO press conference in 2017.

For now, gonorrhea surveillance, education, and prevention will continue to be the main defenses against the arrival of super-resistant gonorrhea, and that likely will remain the case for the foreseeable future.

"We just need to make sure that we're working with our providers, our clinicians, and our public health personnel in educating the general population so that we can try to prolong the time that we have to use the antibiotics we have available," said St. Cyr.

See also:

Mar 27 Public Health England report

Jul 5 Eurosurveill rapid communication

Aug 29 CIDRAP News story "US sees record STD cases, rising gonorrhea resistance"

Jul 6, 2017, CIDRAP News story "Global officials warn of pan-resistant gonorrhea"