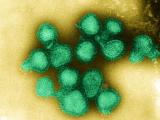

Jun 29, 2009 (CIDRAP News) – To outside observers, the novel H1N1 virus spreading quickly to every corner of the globe must seem like it came out of nowhere, but the organism is a fourth generation of the 1918 pandemic virus and comes from an H1N1 family tree that is colorful and complex, according to two historical reviews that appear today in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).

Understanding the history of swine influenza viruses, particularly their contribution to the 1918 pandemic virus, underscores the need to better comprehend zoonotic viruses as well as the dynamics of human pandemic viruses that can arise from them, the authors report in an early online NEJM edition.

The world is still in a "pandemic era" that began in 1918, wrote three experts from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), senior investigator David Morens, MD, medical epidemiologist Jeffery Taubenberger, MD, PhD, and NIAID director Anthony Fauci, MD.

The 1918 virus has used a "bag of evolutionary tricks" to survive in humans and pigs and to launch other novel viruses, they wrote. "The 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus represents yet another genetic product in the still-growing family tree of this remarkable 1918 virus."

The novel H1N1 virus' complex evolutionary history involved genetic mixing within human viruses and between avian- and swine-adapted viruses, gene segment evolution in multiple species, and evolution from the selection pressure of herd immunity in populations at different times, the group wrote, adding. "The fact that this novel H1N1 influenza A virus has become a pandemic virus expands the previous definition of the term,"

Though any new virus is unpredictable, Fauci and his colleagues wrote that in this pandemic era, severity appears to be decreasing over time, with an evolutionary pattern that appears to favor transmissibility over pathogenicity.

Two researchers from the University of Pittsburgh, in a review article on the emergence of H1N1 viruses, wrote that viral adaptation to a new host species is complex, but the 1918 influenza A H1N1 virus was unusual because it emerged from a bird source in pigs and humans at the same time. In contrast, researchers have said the new H1N1 virus probably emerged from swine to humans. The authors are Shanta Zimmer, MD, from the medical school, and Donald Burke, MD, from the graduate school of public health.

Previous research suggests that antibody specificity against the 1918 human influenza virus diverged quickly from swine influenza viruses, and genetic differences in hemagglutinin (HA) continue to show the same type of rapid divergence between human and swine viruses, they wrote.

Researchers still don't know why H1N1 retreated in 1957 for the next 20 years, though likely factors include high levels of existing homologous immunity plus the sudden appearance of heterologous immunity from a new H2N2 strain, Zimmer and Burke wrote.

Cross-species transfers of swine influenza H1N1 cropped up a few times over the next two decades, and human H1N1 didn't surface again until 1977, presumably because of a laboratory accident in the former Soviet Union. This event marked a first in interpandemic history: the cocirculation of two influenza A viruses.

The authors wrote that it's difficult to predict how well the pandemic strain will compete against the seasonal H1N1 virus. Both viruses share three gene segments with their remote 1918 descendant: nucleocapsid, nonstructural, and HA. They pointed out that studies of B-cell memory response in 1918 pandemic survivors showed that the neutralizing body against HA was specific and long-lasting.

Cell-mediated immunity may also affect competition between the two viruses, the authors wrote. Though it's not clear if cytotoxic T lymphocytes clinically protect humans, they have been shown to reduce viral shedding, even in the absence of antibodies against HA and neuraminidase.

"Cytotoxic T lymphocytes that are generated by seasonal influenza viruses against conserved epitopes might provide heterotypic immune responses that could dampen transmission, even in the absence of measurable antibody protection," Zimmer and Burke wrote.

Morens DM, Taubenberger JK, Fauci AS. The persistent legacy of the 1918 influenza virus. N Engl J Med 2009 Jul 16;361(3):225-29 [Full text]

Zimmer SM, Burke DS. Historical perspective—emergence of influenza A (H1N1) viruses. N Engl J Med 2009 Jul 16;361(3):279-85 [Full text]