Closing the border separating San Diego and Tijuana, Mexico, during the COVID-19 pandemic didn't stop drug tourism and may have increased the spread of HIV, concludes a study posted in The Lancet Regional Health Americas.

From October 2020 to October 2021, a team led by University of California at San Diego (UCSD) researchers recruited 612 adults from the street in three different groups: those who live in San Diego and cross the border to use injectable drugs in Tijuana; San Diego residents who use drugs in San Diego; and those Tijuana residents who use drugs in Tijuana.

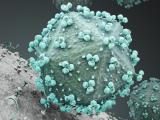

The team also isolated the HIV virus, sequenced its RNA, assessed the genetic diversity and viral relationships, identified case clusters near the border, and estimated the timing of cross-border spread. Participants answered questions about their demographics, drug use, sexual behavior, sexual identity, and border crossings and gave blood samples and underwent HIV and hepatitis C tests every 6 months.

"If two or three people have viruses that are very similar to each other, we can assume that the transmission event happened more recently, because there is not enough evolution between these different viruses from these different people," senior author Tetyana Vasylyeva, DPhil, of the University of California at Irvine, said in a UCSD press release.

From March 2020 to November 2021, the United States and Mexico suspended all nonessential travel across their borders.

Injectable drugs, sex work

Of the 612 participants, 26% were women, 9% were sex workers, 8% had HIV at baseline, and the median age was 43 years. The use of injectable drugs and sharing injection equipment raises the risk of HIV infection. The San Diego–Tijuana border is a major drug-trafficking route for the movement of heroin, fentanyl, methamphetamine, and cocaine into the United States from Mexico, the authors noted.

"Small amounts of drugs have been partially decriminalized in Mexico since 2009 for personal consumption, and drugs are perceived to be cheaper and more widely available in Tijuana compared to the US," they wrote.

"Tijuana has a zona roja where sex work is legal; in this region, cross-border drug use (CBDU) and cross-border sex are major drivers of bidirectional cross-border mobility and are linked to potential HIV-1 risk behaviors such as sharing injection drug paraphernalia and paying for sex," they added.

Disruption of drug-treatment, syringe services

During the study, nine people tested positive for HIV, most of them during the COVID-19 pandemic. "Nine sounds like a small number, but it's actually quite a lot of people because in the US, HIV incidence is relatively low," lead author Britt Skaathun, PhD, said in the release. "We were surprised to see this change in HIV status in such a short amount of time and wanted to look more closely at these clusters."

Mobile harm reduction services and coordination with municipal HIV programs to initiate anti-retroviral therapy and pre-exposure prophylaxis are needed to reduce transmission.

Of 16 clusters, 9 (56%) had sequences from both the United States and Mexico. The timing of the three earliest mixed-country dyads before the pandemic overlapped with the COVID-19 border closure in 2020. One mixed-country cluster kept growing during the border closure, eventually reaching 15 people, 7 of whom were sex workers. "This shows that efforts to build a higher wall or policies to stop immigration will not mitigate HIV spread," Vasylyeva said.

In effect, the border closure was a structural risk factor for harm, Skaathun said: "The Frontera [border region] is one integrated community that is not defined by place of residence. Efforts to end the HIV epidemic in the U.S. also need to be integrated by extending to Tijuana."

The study authors said COVID-19 mitigation measures such as border closures may have resulted in diminished access to services and an oversupply of drugs in Tijuana, leading to the disruption of drug-treatment and syringe-service programs on both sides of the border.

"People who engage in CBDU may be critical to engage in HIV-1 risk reduction interventions as they are situated in HIV-1 molecular clusters that include residents from both sides of the border," they concluded. "Mobile harm reduction services and coordination with municipal HIV programs to initiate anti-retroviral therapy and pre-exposure prophylaxis are needed to reduce transmission."