Even if you follow news about infectious diseases and outbreaks caused by rare pathogens, you may have missed an update from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) about a rare respiratory infection in October.

The Oct 22 CDC announcement regarded the identification of a possible cause of an outbreak of melioidosis in the United States that had sickened four people, two of whom died, earlier in the year. Up until that point, the source of the outbreak had been a mystery.

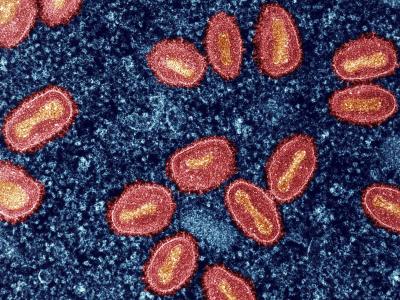

As it turns out, the source of the four cases of melioidosis—an infection caused by the bacterium Burkholderia pseudomallei—was an aromatherapy room spray found in the home of one of the patients. It was, as a CDC official noted in the press release, the "proverbial needle in the haystack," just one of the thousands of things people might come into contact with in and around their homes.

Maria Bye, MPH, an epidemiologist with the Minnesota Department of Health who led the department's investigation into one of the cases, likened it to an episode of the TV show "House," where the lead character tackles medical mysteries.

"We had four cases from across the country who didn't have a lot in common, and we couldn't really find anything linking them," Bye told CIDRAP News. "So we really didn't even know where to begin with it."

Compared with the COVID-19 pandemic, which has dominated our every waking moment for the past 20 months, the meliodosis outbreak was minute. But it could have been worse. And during what has been a very tough time for everyone who works in public health, the identification of the culprit—and the effort that went into the investigation—is a reminder of the critical role that public health investigators play in preventing outbreaks.

"This is an outstanding example of what we call 'shoeleather epidemiology,' basically not giving up until you find the cause," said Mike Osterholm, MPH, director of the University of Minnesota's Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, which publishes CIDRAP News.

A rare pathogen

The mystery behind the outbreak began with the disease itself. Melioidosis is incredibly rare in the United States, with only 12 cases reported annually. And because the symptoms it causes—cough, shortness of breath, fatigue, nausea—are nonspecific, it's often confused with other respiratory ailments.

"Melioidosis has often been described as the 'great mimicker,'" said Julia Petras, MSPH, an Epidemic Intelligence Service officer with the CDC's Division of High Consequence Pathogens and Pathology. "It's commonly misdiagnosed as tuberculosis."

Its rarity in the United States stems from the fact that the B pseudomallei bacterium is most commonly found in moist soil and water in South and Southeast Asia and northern Australia, where melioidosis is considered endemic. Which is why one of the first things investigators look at with US cases is travel history.

"When we investigate any case of melioidosis that comes through, the first question is 'have you traveled to an endemic area?'" said Petras.

But the answer to that question added another layer to the mystery. None of the first three patients—the first of whom was identified in Kansas in March, the other two in Minnesota and Texas in May—had any history of recent travel outside the United States, and they had no connection to one another. And only two of the patients had any of the known risk factors for the disease, which include diabetes, liver disease, and chronic lung disease.

That's when the investigators turned to whole genome sequencing of the bacteria isolated from the patients. By providing a nearly complete reading of the millions of units that make up a bacterial pathogen's DNA, whole genome sequencing enables investigators to determine how closely related bacterial isolates from different patients are, if at all, and whether they may be linked to a common source.

That's when the investigators turned to whole genome sequencing of the bacteria isolated from the patients. By providing a nearly complete reading of the millions of units that make up a bacterial pathogen's DNA, whole genome sequencing enables investigators to determine how closely related bacterial isolates from different patients are, if at all, and whether they may be linked to a common source.

When the CDC sequenced the bacteria from the Kansas patient, who had died, they found that the genetic fingerprint was similar to strains found in South Asia. Bacterial isolates from the next two cases—identified in Texas and Minnesota in May—were nearly identical, as was the isolate from the fourth patient, who was identified in Georgia, post-mortem, in July. That indicated a common source of infection that somehow was linked to South Asia.

"We were able to see that [the isolates] were considered to be clonal to one another, meaning the patients must have been exposed to the same source," Petras said.

But that finding on its own still left the big question unanswered. What was the source?

"That's when you have to dig a little deeper to find out what could be connecting them," said Bye. "There were a lot of different hypotheses and things we were considering, but we didn't even have a front-runner for what it could be for a while."

A wide net

The investigators then began to cast a pretty wide net for the source, according to Petras. Bye said the CDC suggested they go to the Minnesota patient's home and investigate any imported house plants or pets they may have that could harbor the bacteria. Pet fish were one possible source, since B pseudomallei had on previous occasions been isolated from aquariums. But since the patient, a man in his mid-50s, had been in the process of moving, Bye said, there were limited items to sample.

They then started looking more closely at potentially contaminated items like food, tea, and personal care products. "We knew there was a contaminated product from South Asia involved," Petras said. "We still were taking environmental samples, just to do our due diligence, but our focus was definitely on products."

But one of the challenges with melioidosis is that, because the symptoms generally appear 3 to 4 weeks after exposure, investigators have a really wide timeframe to explore. You're asking patients to try and remember a product they may have come into contact with weeks before.

After the patient in Georgia was identified, however, the net became a bit narrower. While initial presentation for the four patients ranged from cough and shortness of breath to weakness, fatigue, and nausea, some also reported neurological symptoms. Petras said that got investigators thinking more about route of transmission, and how the bacteria could travel to the brain.

"That's when we started thinking maybe it was inhaled," she said.

Investigators from the CDC and the Georgia Department of Public Health went to the home of the Georgia patient in August and took several samples, then returned again in October, after the patient had died.

It was at the second visit, after more than 100 samples from products, soil, and water from in and around all four patients' homes had been collected and tested, that they zeroed in on an aromatherapy spray—the Better Homes & Gardens Lavender & Chamomile Essential Oil Infused Aromatherapy Room Spray with Gemstones—sold at Walmart stores and manufactured in India.

A few weeks later, lab testing conducted by the CDC identified B pseudomallei in the spray, and the Consumer Product Safety Commission and Walmart initiated a recall of the product, along with other scents in the line. A few weeks after that, genomic sequencing revealed that the genetic fingerprint of the B pseudomallei strain in the spray matched that of the Georgia patient—confirming it as the source of the infection—as well as the three other patients.

"They're all considered identical strains," Petras said.

Bye said the source remained a true mystery until the room spray tested positive for B pseudomallei. "There really wasn't an 'aha' moment," she said. "We were all waiting for a lightbulb to go off over our heads, but that never really happened."

While the investigation is still ongoing, Petras says they've already learned some important lessons. One is that risk factors and potential sources of exposure have expanded. "Who would have thought that a bacterium from India could travel in a product and infect people here?" she said. "That's an important takeaway that everyone should be aware of."

She also credited state health department investigators, along with the families of the four patients, for helping stem what could have been a wider outbreak.

"We would not have found the source, and potentially prevented illness and death in people, if it wasn't for the cooperation of these families, who let us go into their homes multiple times and sample a laundry list of products," she said. "This has been a very heavy lift for everyone involved."

Osterholm said the investigation harkens back to the classic epidemiologic tale of John Snow, the young English surgeon who discovered that a water pump was the source of an 1854 cholera outbreak in London. The removal of the pump handle quickly brought that epidemic under control.

"We would have had many additional cases based on this source, had it not been found," he said. "So it's not just a story about the cases that had occurred, but it's also about the future cases that are now prevented because of this discovery."