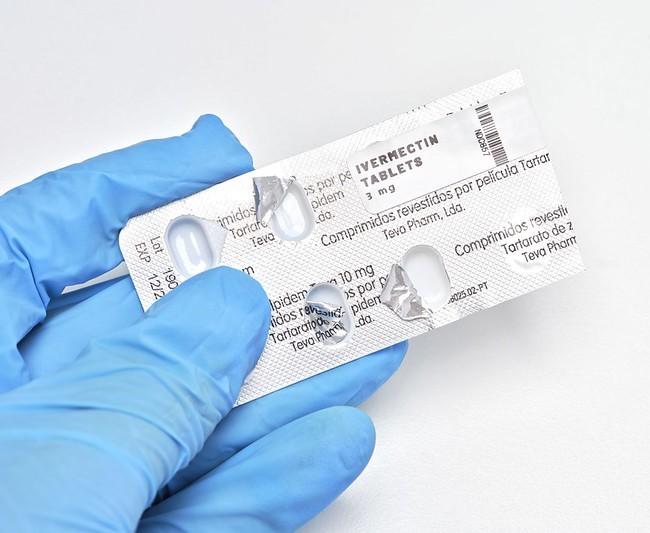

A study of COVID-19 patients at clinics in 12 Brazilian cities found that treatment with ivermectin—an antiparasitic drug—didn't prevent hospital admission compared with those in the placebo group.

Early in the pandemic, before treatments were available, some looked to repurpose existing drugs such as ivermectin as possible treatments. Some of ivermectin's proponents pushed the drug, despite inconclusive evidence and a lack of high quality studies.

As the drug became a politicized hot-button issue, some patients treated themselves with animal versions of ivermectin at toxic doses.

Today, the large size of the randomized, placebo-controlled trial, known as a gold standard for evaluating treatments, tilts the weight of evidence away from ivermectin benefits for COVID-19, according to the study authors. The team published its findings yesterday in the New England Journal of Medicine.

No benefit for any clinical outcome

The study was part of a larger double-blind trial that looked at various interventions, including ivermectin, across 12 sites in Brazil's Minas Gerais state. For the ivermectin arm of the study, researchers enrolled 3,515 lab-confirmed symptomatic COVID-19 patients, of which 679 were randomly assigned to receive ivermectin, 679 were assigned to placebo, and 2,157 were assigned to another intervention.

Those in the ivermectin group received it once a day for 3 days at 400 micrograms per body weight, which the authors said in the supplementary appendix was a relatively high dose, ensuring its safety compared with most earlier trials.

When the researchers weighted the two groups, 100 (14.7%) patients who received ivermectin had a primary outcome that included hospitalization or lengthy evaluation in the emergency department, compared with 111 (16.3%) the placebo group. They also found no impact on secondary outcomes, such as viral clearance, duration of hospitalization, time to clinical recovery, need for mechanical ventilation, or death from any cause.

The authors wrote that earlier meta-analyses that combined the results of smaller studies were inconsistent on potential benefits for ivermectin, and they noted that their trial was larger than the number of all of the combined studies.

"The results of this trial will, therefore, reduce the effect size of the meta-analyses that have indicated any benefits," they said, adding that one earlier study was withdrawn due to suspected malfeasance and that others had quality problems.

The new findings are consistent with an earlier World Health Organization recommendation against ivermectin use.

Weighing the clinical implications

In a recorded NEJM discussion yesterday with three of the journal's editors, who weren't involved in the study, Lindsey Baden, MD, deputy editor, said that data show no signal of clinical activity in a properly conducted clinical trial. He said it's better to use active treatments rather than those we want to work but have no evidence to back them up.

Eric Rubin, MD, PhD, editor-in-chief, said similar to the early days of HIV treatment, when there were few treatments, repurposed drugs were very attractive but became less so as better therapies emerged.

Now for COVID-19, there are therapies. "None of them are magic, but some of them are awfully good," he said. "We can now say we have something to offer people."

He said he worried, though, about the idea of replacing vaccines that prevent disease with treatment. "I don't think of these as alternative," he said. "They're just an adjunct to good prevention."