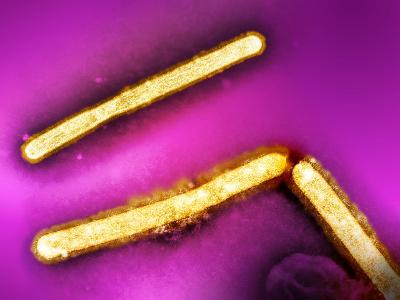

During the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, azithromycin was one of the virus's unproven, potential treatments, and the resulting shortage forced US doctors to rely on the substitute drug clarithromycin as an adjunct surgical prophylaxis for preventing endometritis in non-elective cesarean deliveries. Now, new research findings reveal that the option is a safe alternative.

In a recent study published by PLOS One, 4.5% of healthy women who were given clarithromycin and needed cesarean deliveries developed endometritis compared with 11.2% of those who didn't receive any adjunct macrolide prophylaxis (crude analysis, P = 0.025).

Postpartum endometritis is a womb infection with a 1% to 3% incidence rate after vaginal delivery, but anywhere from a 13% to 90% incidence rate after cesarean delivery, according to Medscape.

Potentially greater efficacy in black, young women

The researchers included all the applicable patients from Mar 23 to Jun 1 at the selected hospital sites in New York and New Jersey. Women received 500 milligrams of clarithromycin orally 30 minutes before cesarean delivery began, so by default, those who were part of the control study did not take oral medications, did not have a provider who paid for the treatment, or did not have adequate time between drug administration and surgery. Of 240 women who met the inclusion criteria, 133 received clarithromycin and 107 received no adjunct macrolides.

Study data showed clarithromycin led to a 66% decreased risk of developing endometritis compared with the control group, and after adjusting for demographic factors including race, body mass index, and age, the results suggested a 67% decreased risk (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.12 to 0.95 and 0.11 to 0.97, respectively). No treated patients had severe adverse effects such as hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, cardiac arrhythmias, or gastrointestinal symptoms.

Secondary outcomes were meconium-stained amniotic fluid and neonatal conditions, such as intensive care unit admission, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and sepsis, each with statistically insignificant results. For instance, while 16.5% of clarithromycin-treated mothers had meconium-stained amniotic fluid, a sign of possible meconium aspiration syndrome, compared with 13.1% of the control group, the p-value was 0.456.

Further data stratification suggested that the 48 black women treated with clarithromycin had an 87% decreased risk of endometritis compared with the 55 white women (95% CI 0.08 to 0.83, unadjusted), and women between 18 and 29 years old had 79% decreased risk (95% CI 0.06 to 0.80, unadjusted). The data table did not say how many women were in the latter category.

"These findings suggest that administration of clarithromycin for adjunctive surgical prophylaxis for non-elective cesarean deliveries may be a safe option that may provide suitable endometritis prophylaxis in cases where azithromycin is unavailable," the researchers write, conceding that a larger study would yield more definitive conclusions. Other possible adverse outcomes, such as surgical site infection, were not measured.

More substitute therapies mean more needed research

While this study may depict clarithromycin as a viable substitute for azithromycin, because it does not compare the two directly, the researchers don't know how much more or less effective this treatment is, said David Margraf, PharmD, MS, Resilient Drug Supply Project (RDSP) pharmaceutical research scientist at the University of Minnesota. (RDSP is a division of CIDRAP.)

The researchers also acknowledged this, saying they could not incorporate azithromycin into the study because of supply availability. At best, they pointed to the 2016 New England Journal of Medicine study that helped galvanize the use of azithromycin in cesarean deliveries. In that study, 6.1% of 1,019 women treated with azithromycin experienced postpartum endometritis compared with 12.0% of 994 women treated with a placebo.

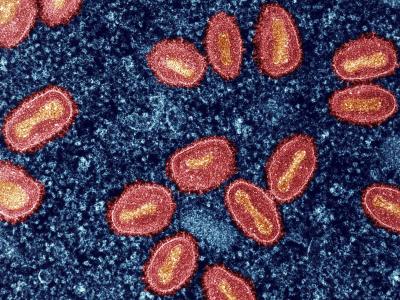

Stockpiling and hoarding were two of the main drivers of azithromycin’s US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-declared shortage, according to the researchers, and BioSpace reported that the antibiotic had a 170% order increase in March and a fill rate of 60% in April.

Eventually, though, studies came out disproving azithromycin's ability to treat COVID-19, triggering the end of the study period and a decline in demand that has not been enough to completely resolve the drug shortage. "This situation should prompt readers to maintain caution regarding the use of experimental drugs without high-quality evidence on a large scale in cases where little is known about an emerging disease," write the researchers.

"The pandemic and its associated drug shortage have led researchers to explore alternate treatment options," Margraf said. "Patients are being given other therapy options instead of the preferred drug with known effectiveness and safety in this patient population." Even though the unprecedented demand for azithromycin has died down, the root of the issue—the unknown consequences and the increased risks from using untested drug substitutes—remains as long as drug shortages remain.

Azithromycin tablets have been in shortage since Apr 14, according to the FDA, and injections have been declared to be in shortage by the American Society of Health-system Pharmacists since Jan 14, 2018.