The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has published updated tuberculosis (TB) screening and treatment guidelines, including recommendations on testing at-risk adults for latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI).

The recommendations were published yesterday in JAMA. The USPSTF updated its 2016 guidelines by commissioning a systematic review on LTBI screening and treatment in asymptomatic adults at primary care visits and on the accuracy of screening tests.

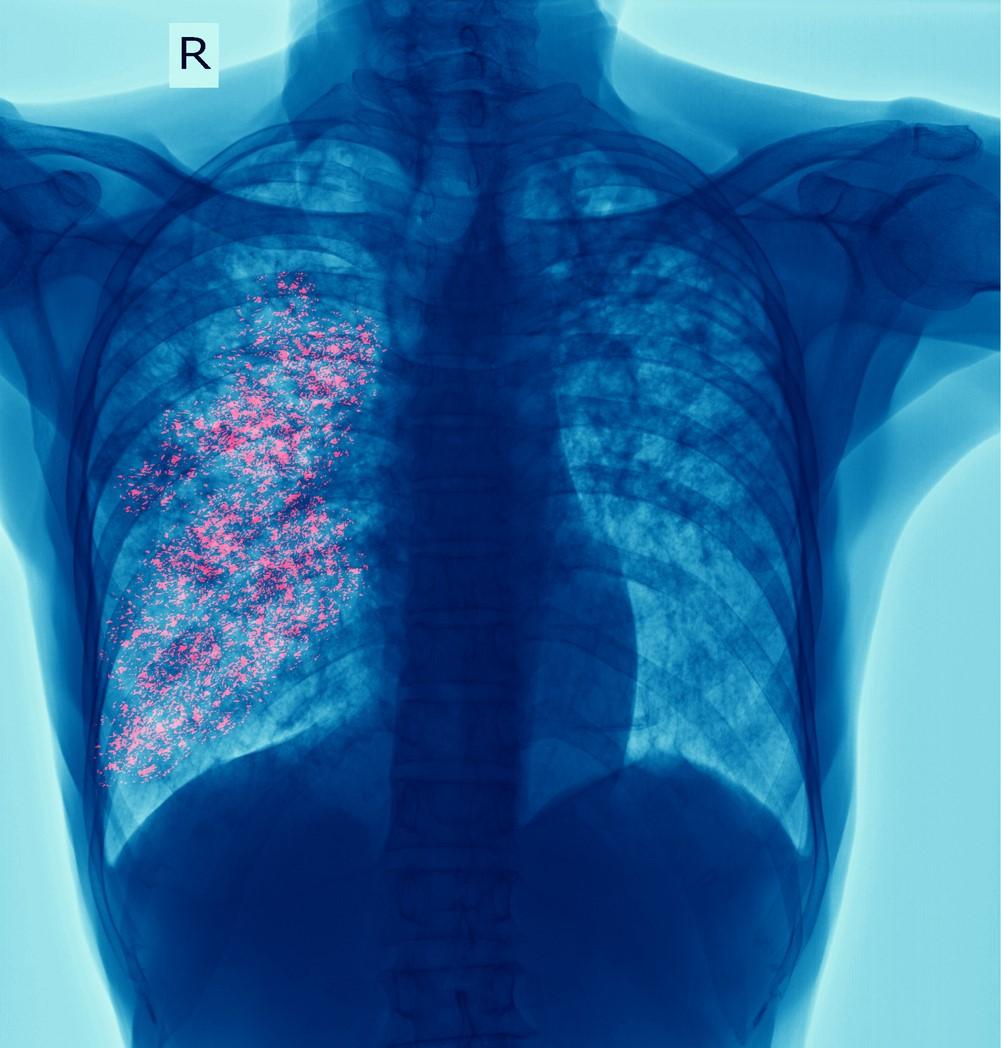

Active TB, which may be infectious, and LTBI, which is asymptomatic and not infectious but can progress to active disease, are preventable respiratory infections. The precise prevalence of LTBI is difficult to determine, the authors said, but the estimated prevalence is about 5.0%, or as many as 13 million people.

"Approximately 30% of persons exposed to Mycobacterium tuberculosis will develop LTBI and, if left untreated, approximately 5% to 10% of healthy, immunocompetent persons will progress to having active tuberculosis disease," the authors wrote.

People most at risk include those with certain medical conditions, healthcare workers, residents of congregate-living settings (eg, correctional facilities, homeless shelters), former residents of countries with high TB prevalence, and Asian, Black, Hispanic, Native American/Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander populations. Rates vary by geographic location and housing situation, suggesting an association with social determinants of health.

Screening, treatment, research

The updated USPSTF recommendations include:

- Screening: The researchers noted two types of screening tests for LTBI: the tuberculin skin test (TST) and the interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA). The TST requires trained personnel to inject purified protein derivative into the skin and interpret the response no more than 48 to 72 hours later. For IGRA, a single venous blood sample is taken to measure the CD4 T-cell response to specific M tuberculosis antigens and to process samples within the next 8 to 30 hours. "Consistent with CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] guidelines, testing with IGRA may have advantages over TST for persons who have received a BCG [bacille Calmette-Guerin] vaccination, because IGRA does not cross-react with the vaccine, and also for persons who may be unlikely to return for TST interpretation," the authors wrote. Both TST and IGRA are moderately sensitive and highly specific for LTBI. Diagnosis of LTBI relies on further clinical assessment of positive screening results and on ruling out active TB. Clinical workup consists of medical history taking, physical exam, chest radiography, and other lab tests. "Given regional variations in the local populations considered at increased risk for tuberculosis, clinicians may consult their local or state public health agency for additional details on specific populations at increased risk in their community," according to the recommendations.

- Screening interval: Because the task force found no evidence on the optimal frequency of LTBI screening, it suggested basing the timing on risk factors. "Screening frequency could range from 1-time only screening among persons at low risk for future tuberculosis exposure to annual screening among those at continued risk of exposure," the report said.

- Treatment: Several antibiotics are available for the treatment of LTBI, including isoniazid. This drug was the first shown to prevent progression to active TB, but concerns about liver damage and drug resistance stemming from low adherence and long treatment courses have prompted recommendations of shorter courses that can be used in combination with other medications such as rifapentine and rifampin.

- Areas for further research: The authors called for studies on the accuracy of risk-assessment tools to help clinicians identify those at increased risk for LTBI and those who should be screened. Other research should focus on which populations should receive repeat screening for LTBI and how often, as well as on which screening strategies are more effective for specific patient groups.

- Recommendations from other societies: Joint guidelines recommend screening for LTBI "in early pregnancy for women at high risk for tuberculosis, including those with recent tuberculosis exposure, HIV infection, risk factors increasing risk of progression to active disease (such as diabetes, lupus, cancer, alcoholism, and drug addiction), use of immune-suppressing drugs such as tumor necrosis factor inhibitors or chronic steroids, kidney failure with dialysis, homelessness, living or working in long-term care facilities such as nursing homes and prisons, being medically underserved, and being born in a country with high prevalence of tuberculosis," the report said.

- Patient information: JAMA has also published information for patients on LTBI screening.

Overcoming operational challenges

In a related commentary, Priya Shete, MD, MPH, of the University of California; Amy Tang, MD, of North East Medical Services in San Francisco; and Jennifer Flood, MD, MPH, of the California Department of Public Health, said that healthcare providers and systems need to overcome operational barriers to successful LTBI screening and treatment.

"Currently most US residents with LTBI are unaware of their infection status and remain untreated," they wrote. "In addition, primary care clinicians are often unaware of who and how to test and treat. Clinician and health delivery systems education needs to be coupled with culturally sensitive outreach, education, and care linkage in at-risk communities."

Currently most US residents with LTBI are unaware of their infection status and remain untreated. In addition, primary care clinicians are often unaware of who and how to test and treat.

Shete and colleagues recommend supporting front-line staff by integrating TB prevention into best practices and highlighting care gaps. "Enabling provision of tuberculosis preventive care through the electronic health record may address barriers to provision of care that many clinicians face in busy primary care practices," they wrote.

In a JAMA Network Open commentary, Dick Menzies, MD, of McGill University Health Centre in Montreal, said that TB preventive treatments should be short, simple, and safe. "Ideally, the regimen should be safe enough that no monitoring is required except to bolster adherence," he wrote. "Self-administered therapy may be more feasible in many settings and populations, particularly office-based practice."

Insurers also need to cover TB services, Menzies said: "Reimbursement for preventive services is not a trivial issue, although the grade B classification by the USPSTF for this recommendation facilitates private insurers’ reimbursement."