The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says 13 cases of Candida auris, an emerging drug-resistant yeast that can cause fatal invasive infections, have been identified in the United States.

In today's Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), investigators describe seven C auris cases that occurred from May 2013 to June 2016. The cases involve patients at hospitals in four states—New York, Maryland, Illinois, and New Jersey—who had been hospitalized with serious underlying medical conditions. The other six cases are still under investigation.

The announcement comes 3 months after the agency warned US healthcare facilities about the emergence of the serious fungal infection, which was first identified in the ear of a Japanese patient in 2009 and since then has been identified in patients in several other countries. The CDC received the case reports after that clinical alert was issued.

In the countries where it has previously been identified, C auris has most commonly caused healthcare-associated infections such as bloodstream infections, wound infections, and ear infections and has been associated with high mortality. CDC investigators report that 5 of the US patients had bloodstream infections, 1 had a urine infection, and 1 had an ear infection. The median time from hospital admission to detection of the infection was 18 days.

Four of the patients died, but it is unclear if their deaths were caused by the C auris infection.

"This is a serious global health threat for which we want to rigorously prepare for in the United States," Tom Chiller, MD, MPHTM, chief of the Mycotic Diseases Branch at the CDC, told CIDRAP News.

Concerns about resistance

There are several major concerns about C auris. One is that isolates from other countries have shown varying levels of resistance to all three major classes of antifungal medicines used to treat Candida infections—including azoles, echinocandins, and polyenes. That raises the prospect, Chiller said, of infections that are "very challenging to treat."

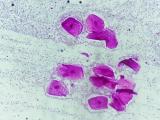

Another issue is that C auris is difficult to identify using common biochemical methods, so there is a concern it can go unrecognized and potentially improperly treated. "We've been trying to work with laboratory communities across the US to communicate that message," Chiller said.

The good news is that in the seven cases investigated by the CDC, isolates showed resistance to at least one class of antifungal drug, but none were resistant to all three classes. But five of the seven reported isolates were either misidentified as Candida haemulonii or simply as Candida, and were not correctly identified until they were analyzed at a reference laboratory.

There's also a concern that C auris can be transmitted in the healthcare environment, which makes it different from other Candida infections, which tend to be isolated. And the data in the MMWR report appear to support that fear.

Whole-genome sequencing showed that in two pairs of patients—one pair at a hospital in New Jersey, the other at a hospital Illinois—the isolates were identical. And the patients weren't at the hospitals at the same time, which means the infections weren't transmitted between the patients, but were likely acquired from the healthcare environment. In addition, isolates were found on multiple surfaces at one patient's hospital.

"That is very concerning to us, when it comes to a multidrug-resistant organism," Chiller said, adding that reports from overseas, including a recent outbreak of 40 C auris cases at a UK hospital, suggest this is how the infection is spreading in other countries.

Potential to slow the spread

The one major difference between the US and overseas cases is that the US cases occurred in patients who were very sick, whereas cases in other countries are occurring in a wider variety of patients—including newborns and healthy patients who are getting infected after undergoing surgery. Chiller suggested this means that we're catching these infections early.

"We have an opportunity to potentially slow the spread, or at least try to contain this as much as we can," he said. "But if nothing is done, it will spread and then start causing infections in a wider variety of patients."

Trish Perl, MD, MSc, an infectious disease expert at the University of Texas Southwest Medical Center, says that while she appreciates the public health value of providing information about an emerging, high-risk infectious disease, she has a lot of unanswered questions about the report and what was going on with the patients identified.

"From a clinical point of view right now, I don't know who to tell to worry about this," Perl told CIDRAP News. "When you have emerging infectious diseases, you need to give clinicians some information so that they can potentially identify those patients and put in place appropriate treatment and prevention precautions."

To control the spread of C auris, the CDC recommends that healthcare providers implement the agency's Standard and Contact Precautions for infectious diseases, and that facilities thoroughly clean the rooms of C auris patients with a disinfectant active against fungi. The CDC says any cases of C auris should be reported to the agency, as well state and local health departments.

See also:

Nov 4 MMWR report

Nov 4 CDC press release

Jun 29 CIDRAP News story "CDC issues warning on multidrug-resistant yeast infection"