A population-wide cohort study in Ontario found that more than 15% of residents colonized with an antimicrobial-resistant (AMR) pathogen went on to develop an infection with the same pathogen, researchers reported yesterday in Open Forum Infectious Diseases.

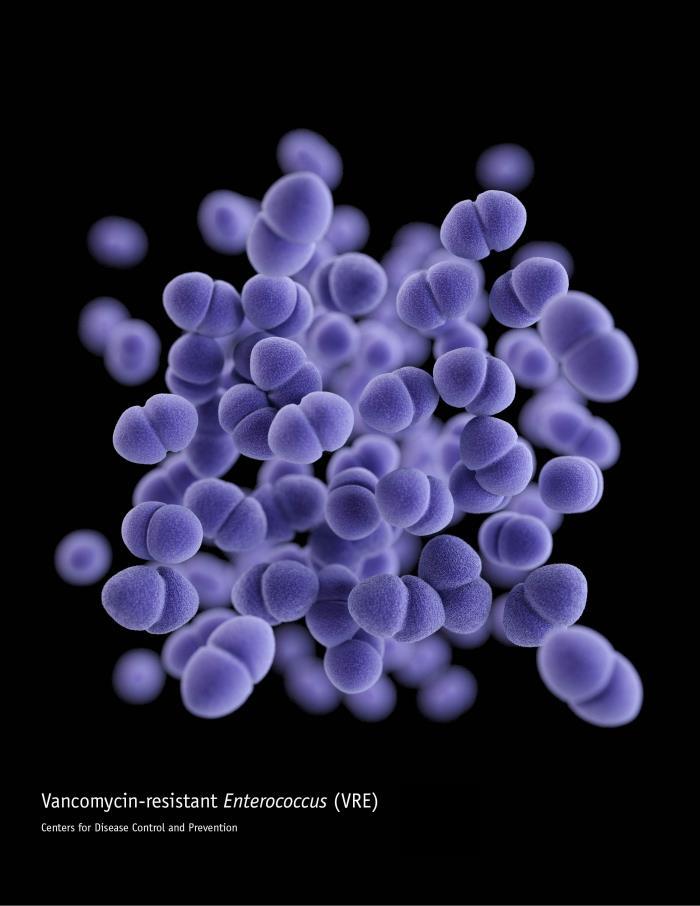

Using population-level health administrative data, a team led by researchers with the University of Toronto investigated the risk of infection among a cohort of residents of Ontario who had a positive surveillance test for a resistant pathogen from January 1, 2017, to December 31, 2021. The specific organisms of interest included methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE), extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing Enterobacterales (ESBL), and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales (CPE). The researchers also examined the effects of age, sex, and healthcare setting of colonization detection on subsequent infection risk.

Among the 69,998 people with a positive surveillance test during the study period, 15.6% subsequently developed a sterile or non-sterile site infection, within a median of 57 days. Infection rates varied between organisms: 18.3% for MRSA within a median of 57 days, 2.8% for VRE within a median of 37 days, 21.5% for ESBL within a median of 71 days, and 20.3% for CPE within a median of 10 days. More than half of all infections occurred within 90 days.

The association of age and sex with infection risk was variable, but a positive surveillance test detected in a hospital was universally associated across all resistant organisms with increased infection risk after colonization compared with the community setting.

Higher risk than previously found

The study authors say the observed rate of infection after colonization is higher than has been found in previous studies, which have been limited by small sample size, single-care settings, and exclusive focus on high-risk patients or settings.

"Colonization with an AMR pathogen has variable infection risk depending on the specific pathogen, but the overall risk is likely higher than what has previously been reported for most organisms, highlighting the importance of detecting colonization from both an infection control and empiric antibiotic selection perspective," they wrote.

They suggest future studies could use the same cohort to examine clinical predictors of progression from colonization to infection.