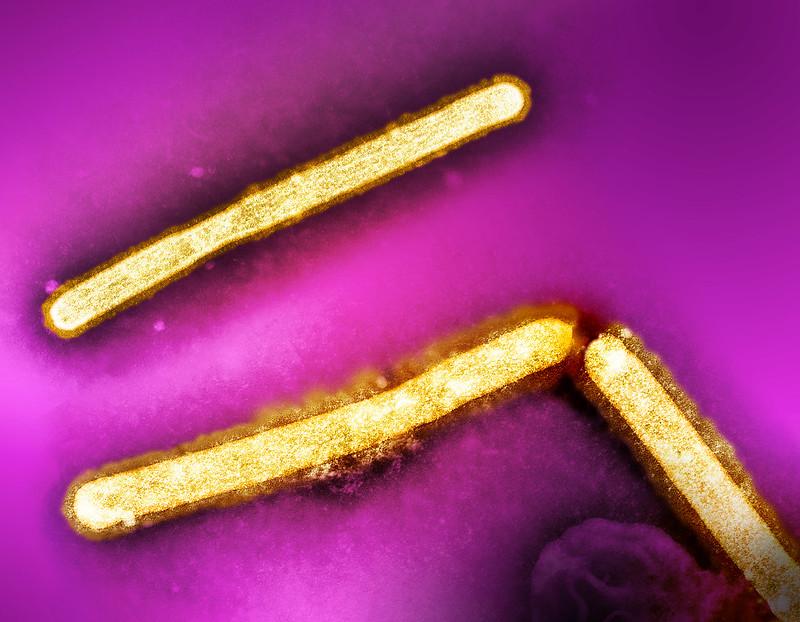

With the public release of 239 recent H5N1 avian flu genetic sequences from US dairy cows and other animals, researchers have already roughly visualized the virus, but they still lack the collection dates and geographic information that would paint a clearer picture.

Meanwhile, the virus was confirmed in another dairy herd in Idaho, raising the number of H5N1 detections to 33, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) said in its update yesterday.

Virus may have circulated undetected for months

Michael Worobey, DPhil, head of the ecology and evolutionary biology department at the University of Arizona at Tucson, on Twitter (X) today detailed the work of an international group of virus evolution and genomic experts who quickly combed through the sequences to identify the DNA, RNA, and protein arrangements of the virus and how the different sequences might be related to each other.

Analysis of the hemagglutinin, neuraminidase, and internal genes hints that the virus hasn't changed much from its introduction into cattle in late 2023 or 2024, he said. The virus could have jumped to cattle once, but the information from the sequences can't rule out multiple introductions, Worobey added.

This reveals massive gaps in our pathogen and surveillance system.

Having collection dates and geographic data with each sequence is crucial for pinpointing when the virus began circulating in dairy cows, along with how and where it is spreading, he said.

There's a strong possibility that the virus has been circulating undetected for months, even before a mysterious illness began affecting dairy cows in February, Worobey said. "This reveals massive gaps in our pathogen and surveillance system."

More evidence of cow-to-cow spread

Commenting on the group's work, Sam Scarpino, PhD, director of artificial intelligence and life sciences at Northeastern University, on X said the genome data strengthen the evidence for cow-to-cow transmission. "This means we need much wider testing of dairy and beef cattle (including testing of asymptomatic cows) to determine how widespread the infections are."

Scarpino said so far, the early analysis shows no obvious changes that would increase the human-to-human transmission risk, but he added that it will take time to fully analyze all the genomes. And though the USDA was slow to post the data, he praised the international science community's speed in mobilizing to analyze what the department shared.