Sept 1, 2006 (CIDRAP News) – The nation's largest public health organization sounded an alarm this week about the public health workforce, citing a current shortage and projecting that the profession could lose up to half of its workers over the next few years.

The American Public Health Association (APHA) outlines the problem in a report titled "The Public Health Workforce Shortage: Left Unchecked, Will We Be Protected?" It was released on the eve of the first anniversary of Hurricane Katrina.

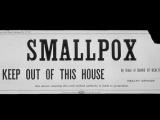

In a press release, the APHA called for immediate action to reverse the shortages, which it said could leave great numbers of Americans vulnerable to a number of health threats.

The report says the number of public health workers decreased from 220 per 100,000 Americans in 1980 to 158 per 100,000 in 2000.

"Our emerging public health workforce crisis comes at a time when Americans are facing a host of risks to their health and safety, from bioterrorism to pandemic influenza and environmental disasters," said Georges C. Benjamin, MD, executive director of the APHA. "At the same time, we risk losing ground on responding to ongoing health problems such as obesity, heart disease and cancer."

Federal funding to recruit and train public health workers must increase dramatically, and states should evaluate their public health workforce needs and establish development and training programs, Benjamin said. "Medical devices and disease tracking instruments are ineffectual without adequately educated and trained workers," he said.

The APHA says that in the next few years, state and federal public health agencies could lose up to half of their workers to retirement, the private sector, and other opportunities. A study from the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials and the Council of State Governments found that the average age of state public health workers is 47 years, 7 years older than the national average for all occupations. Current vacancy rates are as high as 20% in some agencies, and annual turnover rates have reached 14% in some parts of the country.

The most severe shortages were found in epidemiology, nursing, laboratory science, and environmental health, the APHA says.

Although the public health workforce has become more diverse in the past 30 years, there is room for improvement in that area, the report says. Minority group members make up about 25% of the US population but only about 10% of people in the health professions. Increasing diversity in public health work would help reduce many health disparities, because the profession could respond better to the needs of minority populations, according to the report.

The APHA urges several strategies to stem the workforce shortage:

- Establish federally funded scholarship and loan repayment programs modeled after those outlined in the Public Health Preparedness Workforce Development Act, introduced by Sen. Chuck Hagel, R-Neb., and Sen. Richard Durbin, D-Ill.

- Renew investment in federal programs that address the shortage of medical personnel in underserved areas to shore up and diversify public health professions such as epidemiology, environmental health, maternal and child health, and nursing

- Increase financial support for the public health infrastructure

- Enhance leadership development programs

- Expand internship and fellowship programs in agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health.