Oct 16, 2002 (CIDRAP News) In the 1960s, the rate of vaccinia virus transmission from people newly vaccinated against smallpox to nonimmunized people was low, but the rate could be higher today because of medical differences between populations then and now, according to a new analysis by smallpox experts.

American studies done in the 1960s indicate an overall rate of contact vaccinia (vaccinia infection acquired from others) of 2 to 6 cases per 100,000 first-time smallpox vaccinations, according to the report published in today's Journal of the American Medical Association. Eczema vaccinatum (EV), the most common serious complication of smallpox vaccination, occurred at a rate of about 1 to 2 per 100,000 primary vaccinations, the report says. EV involves spreading vaccinial skin lesions in people who have eczema or a history of eczema, usually atopic dermatitis.

The report was written by John M. Neff, MD, of the University of Washington, and three colleagues, including Donald A. Henderson, MD, MPH, who led the campaign to eradicate smallpox in the 1960s and 1970s. "The available data from the 1950s and 1960s show that there is a risk of vaccinia transfer from a primary vaccinee to an unimmunized individual in contact with the vaccinee, but the risk is not large," they write.

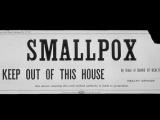

The risk of vaccinia infections in contacts of vaccinees is one of the worries federal health officials face as they consider whether to offer smallpox vaccine to the public as a precaution against possible bioterrorism.

The authors analyzed four large studies conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 1963 and 1968. These included a national survey in each year focusing on deaths related to postvaccinial complications and patients who had been treated for serious complications, plus a survey in each year of all pediatricians in four states for adverse events.

The rates of documented EV cases in contacts of vaccinees in 1963 and 1968 were 8.7 and 10.7 cases per million primary vaccines, respectively, the report says. In nearly all cases of contact vaccinia, the source of the infection was a primary vaccinee. Out of a total of 11.8 million primary vaccinations for the two years, there were 54 EV cases and 2 deaths in 1963 and 60 cases with 1 death in 1968. These cases accounted for about half of all the EV cases reported in the national surveys.

The authors also looked at the rate of what the CDC in the 1960s called accidental infection, meaning vaccinial lesions in the eye, mouth, or elsewhere in the absence of eczema or other preexisting skin conditions. The national surveys showed that accidental infection occurred in contacts at rates of 3.5 per million primary vaccinations in 1963 and 7.9 per million in 1968. These infections occurred in healthy children and were self-limited, the report says.

Most of the contact vaccinia cases occurred in young people: 62% in children under age 5 and about 18% in those between the ages of 5 and 19. The authors also note that the surveys showed no cases of two other serious vaccine complications, progressive vaccinia and postvaccinial encephalitis.

Commenting on the low rates of contact vaccinia, the authors state, "In all of the studies, contact vaccinia required close contact, was an unusual occurrence outside of the home, and occurred rarely as a result of a hospital-related contact."

But several factors could make for a higher rate of contact vaccinia today, the article says. Adverse reactions were probably underreported, in part because EV was a poorly defined condition. The prevalence of atopic dermatitis in US children now may range from 6% to 22%, compared with 3% to 6% three decades ago. Further, more people today have immune system disorders, especially HIV, and they could be at risk for progressive vaccinia.

In addition, the authors say, most people vaccinated against smallpox today would probably shed the virus from the vaccination site for up to 19 days, which is the response seen in those with no or very little immunity. The report implies that in the 1960s, some vaccinations were repeat vaccinations of people who already had immunity, which resulted in less viral shedding and a lower risk of transmission.

The report says that no documented cases of contact vaccinia occurred in hospitals in the 1960s, presumably because of special precautions hospitals took to prevent transmission from vaccinated staff members. Even more caution would be necessary today, because many hospital employees would be first-time vaccinees and more patients have immune disorders, the article says.

Concluding that the risk of contact spread of vaccinia "cannot be predicted," the authors call for caution in any large-scale vaccination program. "A carefully paced and limited vaccination program can be based on specific protocols that are developed to screen, counsel, and monitor for adverse reactions," they state.

Neff JM, Lane JM, Eulginiti VA, et al. Contact vaccinia: transmission of vaccinia from smallpox vaccination. (Commentary) JAMA 2002;288(15) [Full text]