Feb 26, 2004 (CIDRAP News) – A pair of recent studies on variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) raises warning flags about the risk of spreading the disease through blood given by people who are carrying the illness but have no symptoms.

Both reports were published earlier this month in The Lancet. One describes the case, first disclosed last December, of a person in the United Kingdom (UK) who fell ill with vCJD more than 6 years after receiving blood from a donor who was later found to have the disease. The case marks the first instance of possible transmission of vCJD—the human variant of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), or mad cow disease—by blood transfusion.

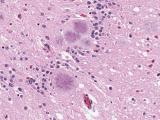

A second report relates how experimenters infected two groups of macaques with a form of BSE by dosing them orally or intravenously with abnormal prion protein, the agent that causes CJD, BSE, and other transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs).

An accompanying commentary says the two articles suggest that blood given by UK donors with preclinical cases of vCJD could spread the disease, despite measures designed to protect the blood supply. "Although the epidemic [of vCJD] may have peaked in the UK, the probable existence of subclinical vCJD carriers raises concerns of an iatrogenic human-to-human wave of vCJD transmission," write Adriano Aguzzi and Markus Glatzel of the Institute of Neuropathology at the University Hospital of Zurich.

In the UK, reports of vCJD cases trigger a search of records for any blood donations by the patient, notes the first of the two articles, by C. A. Llewelyn and colleagues. The person with the possible transfusion-related case was one of 48 people who received a blood component from a total of 15 donors who later became vCJD victims.

The blood recipient experienced the first symptoms about 6-1/2 years after the transfusion; the blood donor fell ill 3-1/2 years after giving blood. The donor was 24 years old when he or she gave blood, and the recipient was 62 at the time of the transfusion in 1996. That was before the UK began "leucodepleting" blood (removing most white cells) in 1998 to reduce the risk of vCJD transmission.

The report says the case could have resulted from eating beef from a BSE-infected cow. But the patient was much older than most vCJD patients, and the authors' statistical analysis indicated that his or her chance of contracting the disease by a route other than the transfusion ranged from 1 in 15,000 to 1 in 30,000. In addition, previous studies showed that blood from sheep that are incubating a TSE can transmit the disease to other sheep.

The authors also write that there is no evidence of transfusion-related transmission of sporadic CJD, despite known cases of exposure. "These data may not, however, be relevant to vCJD because this disease is due to a novel infectious agent in human beings and because the amount of disease-associated prion protein in peripheral lymphoreticular tissues is higher than in sporadic CJD, indicating a different pattern of peripheral pathogenesis."

In the macaque experiment, French researchers sought to examine the transmissibility and tissue distribution of the BSE agent after administering it intravenously or orally. They gave two macaques an oral dose of "macaque-adapted BSE brain homogenate." Three other macaques were given one of three intravenous dosages of the same material. The animals were monitored until they had advanced disease and then humanely killed.

All the monkeys became ill, but the survival time of the IV-injected monkeys was much shorter than that of the orally dosed monkeys (25 to 33 months versus 47 and 51 months), the report says. The injected macaques had about the same survival time as macaques that had been injected intracerebrally with BSE agent in another study.

The BSE agent was distributed similarly in both groups of animals, appearing in the entire intestine, lymphoreticular tissues such as the tonsils and spleen, peripheral motor nerves, and the autonomic nervous system, the report says.

The authors concluded that the IV route "should be regarded as a likely route of contamination for vCJD patients with a medical history involving a transfusion during the period at risk."

In their commentary, Aguzzi and Glatzel write that the finding of possible bloodborne transmission of vCJD, though it may be shocking, is not surprising in view of the evidence of similar transmission in sheep. Given the potential for more such cases, the leucodepletion of blood to reduce the risk may be worth its high cost, they say. "But nobody knows whether leucodepletion is sufficient, or even necessary, for protecting transfusion recipients from vCJD prions."

The two reports also point up the need for reliable, "high-throughput" tests for detecting prion-tainted blood, according to the commentators. They also call for cross-sectional studies to assess the prevalence of prion carriers, even though such research will pose "organizational and ethical problems."

Llewelyn CA, Hewitt PE, Knight RSG, et al. Possible transmission of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease by blood transfusion. Lancet 2004 Feb 7;363(9407):417-21 [Abstract]

Herzog C, Sales N, Etchegaray N, et al. Tissue distribution of bovine spongiform encephalopathy agent in primates after intravenous or oral injection. Lancet 2004Feb 7;363(9407):422-8 [Abstract]

Aguzzi A, Glatzel M. vCJD tissue distribution and transmission by transfusion—a worst-case scenario coming true? (Commentary) Lancet 2004 Feb 7; 363(9407):411-2 [PubMed listing with link to text]

See also:

Dec 19, 2003, CIDRAP News story on suspected bloodborne transmission of vCJD