Aug 4, 2004 (CIDRAP News) California researchers triggered brain disease in mice by injecting a synthetic form of prion protein into their brains, providing what the researchers call "compelling" evidence that prions alone cause diseases like bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD).

The researchers used Escherichia coli to produce normal prion protein, according to their report in the Jul 30 issue of Science. They induced this protein to misfold into amyloid fibrils and then injected the fibrils into transgenic mice, which eventually showed signs of brain disease. When brain material from these mice was later inoculated into other mice, they got sick as well.

"Our results provide compelling evidence that prions are infectious proteins," states the report by a team mostly from the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). Led by Giuseppe Legname, the team included Stanley Prusiner, the discoverer of prions, as senior author.

According to a UCSF news release, Prusiner and colleagues have long maintained that prions, unlike viruses, contain no genetic material (DNA or RNA). Infectious prions form when normal proteins in brain cells lose their corkscrew shape, called an alpha helix, and flatten into "beta sheets," according to the release. The researchers suspect that this happens occasionally in people and animals but that the misshapen proteins are usually removed from brain cells. But sometimes, the researchers hypothesize, the prion triggers a chain reaction of protein misfolding, leading to nerve cell damage and eventually to death.

A related news story in Science says that biologists have tried for years to prove the infectious-prion hypothesis by purifying protein clumps from the brains of diseased animals and injecting them into healthy animals. But they haven't been able to prove that the injections were free of other possible agents. And experiments using synthetic prionsuncontaminated by other brain tissuehaven't consistently triggered disease, according to the story.

Prusiner's group used genetically modified E coli to make prion protein free of brain tissue. They then took a segment of this protein and induced it to misfold into amyloid (waxy) fibrils by putting it in a shaking device, according to the UCSF release. Then they inoculated the amyloid fibrils into transgenic mice.

The mice were of a genetically modified strain that produce the normal version of the same prion protein fragment the experimenters were using, according to the release. The transgenic mice make 16 times as much of this protein as wild-type mice do, which shortens the incubation time when the mice are exposed to infectious prions.

When the mice were still healthy after 300 days, the investigators were ready to call the experiment a failure, according to the release. But at 380 days, one of the mice showed signs of brain disease, and all of the mice had fallen ill by 660 days after the study began. Control mice that had been injected with a saline solution remained well.

An extract of brain tissue from one of the sick mice was then injected into groups of wild-type mice and other transgenic mice. The wild-type mice became ill after a mean of 154 days and the transgenic mice after 90 days, the report states.

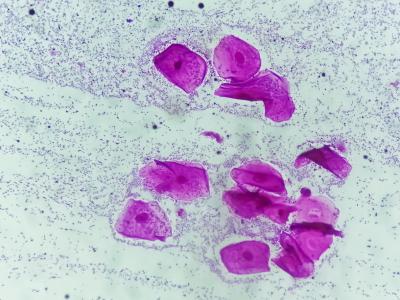

The news release says the findings in the mice injected with synthetic prion material demonstrated the "four hallmarks of prion disease": clinical signs of neurologic dysfunction (ataxia and rigidity), pathologic changes in the brain (sponginess, deposits of abnormal prion protein, astrocytic gliosis), prion resistance to breakdown by protease, and transmission of disease to wild-type and other transgenic mice.

"Our study demonstrates that misfolding a particular segment of the normal prion protein is sufficient to transform the protein into infectious prions," Legname commented in the news release. "A great deal of evidence indicates that prions are composed only of protein, but this is the first time that this has been directly shown in mammals." Legname is an assistant adjunct professor of neurology in Prusiner's laboratory.

In their full report, the authors contend that their success in synthesizing infectious prions shows that such prions can form spontaneously from normal prion protein in mammals. "The formation of prions from recPrP [recombinant prion protein] is sufficient for the spontaneous formation of prions; thus, no exogenous agent is required for prions to form in any mammal," they state.

In the news release, Prusiner said the findings offer an explanation for the sporadic form of CJD, which occurs in about 1 to 2 people per million and is believed to develop spontaneously. He also expressed a belief that sporadic BSE can occur and that increased testing of cattle will reveal it in 1 to 5 cattle per million. The spread of BSE in Britain in recent years has been blamed on the use of cattle feed containing protein from BSE-infected cattle.

The news article in Science cites some doubts about the validity of Prusiner's findings. For example, John Collinge, director of the Medical Research Council Prion Unit at University College London, speculated that the mice might have gotten sick even without any injection of prion protein. He said his group had worked with rodents having 10 times the normal level of prion protein but stopped using them after finding signs of prion-like disease in animals that hadn't been inoculated with anything.

According to the article, Collinge said Prusiner's mice might be primed to suffer brain disease without any prion injection. Inoculating them with synthetic prions might trigger disease, but other stresses might have the same effect, he said.

Legname G, Baskaov IV, Hoang-Oanh BN, et al. Synthetic mammalian prions. Science 2004;30(5):673-6 [Abstract with links to full text and related news story]

See also:

UCSF news release

http://pub.ucsf.edu/newsservices/releases/200407274/