Two large studies that traced the genetic patterns of cholera spread in Africa and the Americas in the seventh pandemic era suggest human actions, rather than environmental factors, likely play the largest role and that in the Americas, local lineages are more likely to trigger sporadic illnesses, and distinct pandemic strains are more likely to cause explosive epidemics.

The reports by two large international research groups were published today in the latest issue of Science. The authors say the findings can help health officials better focus outbreak response steps and gauge their impact.

The seventh cholera pandemic began in 1961 and is still under way. It spread across South Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean. But, until now, experts haven't had a complete understanding of how the disease spreads across continents.

Explosive outbreaks in Haiti in 2010 and in Yemen this year have focused attention on the disease, and a spate of smaller outbreaks are ongoing in several countries in the Horn of Africa and Gulf of Aden region. In Bangladesh, health officials are using oral cholera vaccine campaigns to prevent a large outbreak in newly arrived Rohingya refugees from Myanmar.

Resistant strains rise in Africa

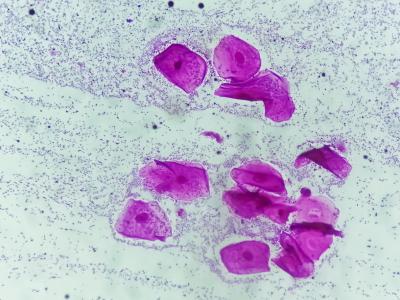

In the African study, researchers poured through genetic data from 1,070 Vibrio cholerae populations that had been isolated across 45 African countries spanning 49 years.

They traced the seventh pandemic expansion on the continent to a single lineage, the El Tor strain, that was introduced mainly from Asia at least 11 times since 1970 into two regions: West and Southeastern Africa. The epidemics that resulted lasted as long as 28 years.

The last five introductions involved multidrug-resistant bacteria sublineages, one of which appeared on the scene in the early 1980s. Resistant organisms replaced the susceptible ones after 2000, which the authors suggested might be linked to mass use of antibiotics over the intervening decades.

For example, they noted that Tanzania's health ministry used tetracycline to curb a 1997 outbreak from a susceptible strain, but 5 months later, 76% of the isolates had become resistant to it and other antibiotics.

Overall, the scientists concluded that the data are consistent with epidemiologic studies, which have shown that human factors, such as environments contaminated from feces of sick patients, play a large role in cholera spread, rather than aquatic reservoirs as the epidemic source.

Factors that influence transmission are complex, they wrote, "but these data provide a detailed genetic context against which we can gauge the impact of interventions on future patterns of disease in this region."

Patterns differ by lineage in Americas

In the second study, a different group of scientists tracked the spread of cholera in Latin America, where two of the world's largest outbreaks occurred following a century-long hiatus. One epidemic began in 1991 in Peru, spreading rapidly to nearly every country in Latin America over the next 6 years, causing 1.2 million infections and 12,000 deaths. The other was Haiti's outbreak, which sickened 797,000 people, about 9,400 of them fatally.

The team used whole-genome sequencing to analyze 252 cholera populations from the Americas over a 40-year period, a group that included both pandemic and local lineages.

Analysis revealed that 164 were from the El Tor strain and 88 were distinct.

The pandemic El Tor strain triggered both major epidemics, while the local lineages were linked to a different illness pattern—sporadic infections or short outbreaks—and only causing widespread illness when they occupied environmental reservoirs.

The findings don't support a hypothesis that the El Nino weather pattern was responsible for introducing cholera to Peru in 1991 or that big disease surges were caused by local cholera lineages, the group wrote.

"An appreciation of the differences between pandemic and local lineages should inform the design of disease control strategies in Latin America," they wrote, adding that public health responses can be tailored, based on understanding which lineages are most likely to spark large epidemics.

See also:

Nov 10 Science study on genomic history of seventh cholera pandemic in Africa

Nov 10 Science study on Vibrio cholerae in the Americas

Nov 10 Science feature story on both studies