Today in the New England Journal of Medicine a study demonstrates that a single subcutaneous (just-under-the-skin) injection of an experimental malaria monoclonal antibody offered up to 77% protection against malaria for children in Mali during a 6-month malaria season.

The monoclonal antibody, L9LS, was developed by scientists at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and was previously shown to offer 80% protection to adults in a phase 1 trial. This study looked at a single injected dose in 6- to 10-year-olds in Mali, a country with high malaria transmission.

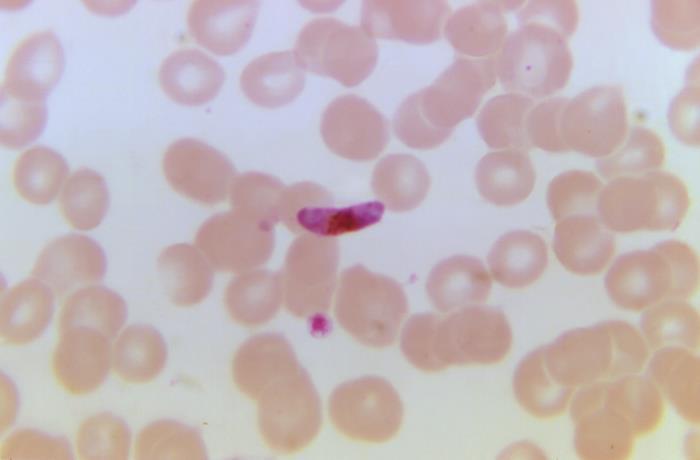

Each year, malaria kills at least 600,000 people, many African children, according to World Health Organization (WHO) data. In 2022, there were 250 million estimated cases of the mosquito-transmitted disease, despite the widespread use of nets and seasonal malaria chemical prevention.

67% to 77% protection

In today's study, researchers assessed the efficacy of two doses, 150 milligrams (mg) and 300 mg, place from July 2022 to January 2023 in healthy children. A total of 75 children each received a 150-mg dose, a 300-mg dose, or a placebo during the malaria season from July 2022 to January 2023.

The authors found that 28% of kids in the 150-mg group developing symptomatic malaria, while just 19% in the 300-mg group did, providing protective efficacy of 67% and 77%, respectively. Fifty-nine percent of children who received the placebo developed symptomatic malaria over the 6-month period, and 81% became infected with the Plasmodium falciparum. That compares with 48% in the 150-mg group and 40% in the 300-mg group.

"The results of this trial support the development of antimalarial monoclonal antibodies in other high-risk populations for whom the WHO recommends chemoprevention, including infants and young children, children with severe anemia after hospital discharge, and pregnant persons," the authors concluded.

No magic bullet for malaria

In an editorial on the study, Trevor Mundel, MD, PhD, of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, writes that while there are several tools in the arsenal to combat malaria, there is no silver bullet, and the threat of growing insecticide resistance looms large.

"Innovation in the areas of monoclonal antibodies, long-acting injectable small-molecule drugs, and next-generation vaccines would give the world such potential tools," Mundel wrote.

In addition to the current promising trial results, monoclonal antibodies offer a useful alternative to seasonal malaria chemical prevention, which is hard to administer for children in low-income countries. A single subcutaneous injection also results in better adherence than a multidose oral program.

Monoclonal antibodies may also outperform malaria vaccines, which also require multiple injected doses and health care touchpoints, Mundel said.

A long-acting monoclonal antibody delivered at a single health care visit that rapidly provides high-level protection against malaria in these vulnerable populations would fulfill an unmet public health need.

In an NIH press release, Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, MPH, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the NIH, said, "A long-acting monoclonal antibody delivered at a single health care visit that rapidly provides high-level protection against malaria in these vulnerable populations would fulfill an unmet public health need."