A systematic review and meta-analysis indicates that adding a low dose of a widely available antimalaria drug to artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) is as safe and effective at blocking Plasmodium falciparum malaria transmission in young children as it is in older children and adults in areas of low- and moderate-to-high transmission.

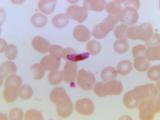

The study, published yesterday in The Lancet Infectious Diseases in advance of World Malaria Day by an international team of researchers, was examining the safety and efficacy of a single dose of primaquine, which kills mature P falciparum gametocytes in infected humans, preventing transmission of malaria to mosquitoes. In 2012, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended adding low-dose primaquine to ACT to aid malaria elimination efforts and limit the spread of artemisinin-resistant strain in areas with partial artemisinin resistance.

While previous research has shown that adding a 0.25-milligram-per-kilogram dose of primaquine to ACT is safe and efficacious in all age-groups, there haven't been enough data to compare safety and efficacy in children younger than 5 years old with older children (ages 5 to 15) and adults. Young children have the highest burden of clinical malaria and are among the most affected by the spread of artemisinin-resistant strains, but there are concerns that adult formulations of primaquine might have adverse impacts, such as hemolytic anemia.

New data support previous findings

Of the 30 studies included in the review, 23 had data on 6,056 patients from 16 countries. Of those patients, 19.3% were children under 5, 46.7% were older children, and 34% were adults—in this study, those 16 and older. Gametocytes were detected in 1,764 (72%) of 2,449 patients, with higher prevalence found in young children compared with older children and adults and moderate-to-high transmission settings compared with low-transmission settings.

Across all age-groups, patients given primaquine were less likely to have gametocytes at day 7 and day 14 than patients given ACT alone. No difference was observed in the effect of single low-dose primaquine on day 7 of gametocyte positivity in young children compared with older children (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.08; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.52 to 2.23) and adults (aOR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0, 20 to 1.25), and between low-transmission and moderate-to-high transmission settings (aOR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.46 to 2.52).

The risk of mosquitoes becoming infected with the use of low-dose primaquine was also no different in young children than in older children (aOR, 1.36; 95% CI, 0.07 to 27.71) and adults (aOR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.01 to 8.84) and between low-transmission and moderate-to-high transmission settings (aOR, 0.18; 95% CI, 0.01 to 2.95).

The safety analysis found that a single primaquine dose did not result in changes in hemoglobin concentration in patients with normal or intermediate glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) activity, with similar effects seen in young children as in older children and adults.

"These findings underscore the need for primaquine formulations suitable for young children, and also provide supportive evidence to expand the use of single low-dose primaquine in regions with a moderate-to-high transmission rate that are threatened by artemisinin partial resistance," the study authors wrote.

WHO warns of stalled progress

The findings were published a day ahead of World Malaria Day, which the WHO marked today with a call for renewed efforts to eliminate the disease. Despite the significant progress that's been made over the past two decades, malaria still sickens an estimated 263 million people a year and causes 600,000 deaths. Ninety-five percent of those deaths are in Africa.

In a news release, the WHO noted that global malaria control efforts have prevented more than 2 billion malaria cases and nearly 13 million deaths since 2000. Introduction and widespread implementation of ACT and expanded use of mosquito nets has played a significant role in those efforts, and the rollout of new malaria vaccines and insecticide-treated netting is expected to save even more lives.

The history of malaria teaches us a harsh lesson: when we divert our attention, the disease resurges, taking its greatest toll on the most vulnerable.

But WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, PhD, warned that progress against malaria is threatened by fragile health systems, climate change, conflict, poverty, and increasing artemisinin and insecticide resistance. In addition, the Trump administration's foreign aid freeze and the dismantling of the US Agency for International Development has contributed to disruption of malaria services in more than half of the 64 countries where malaria is endemic. In March, Tedros said that, if those disruptions continue, countries in Africa could see a significant uptick in cases and deaths this year.

Tedros urged malaria-endemic countries to boost domestic spending on healthcare and called for the replenishment of the Global Fund and Gavi, which have been critical funders of malaria programs and interventions.

"The history of malaria teaches us a harsh lesson: when we divert our attention, the disease resurges, taking its greatest toll on the most vulnerable," Tedros said. "But the same history also shows us what's possible: with strong political commitment, sustained investment, multisectoral action and community engagement, malaria can be defeated."