People pass twice as many viruses to domestic and wild animals than animals pass to people, concludes a study today in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

University College London (UCL) researchers analyzed genomic data on nearly 12 million viruses in 32 viral families using network and evolutional analyses to characterize the mutations behind recent vertebrate species jumps.

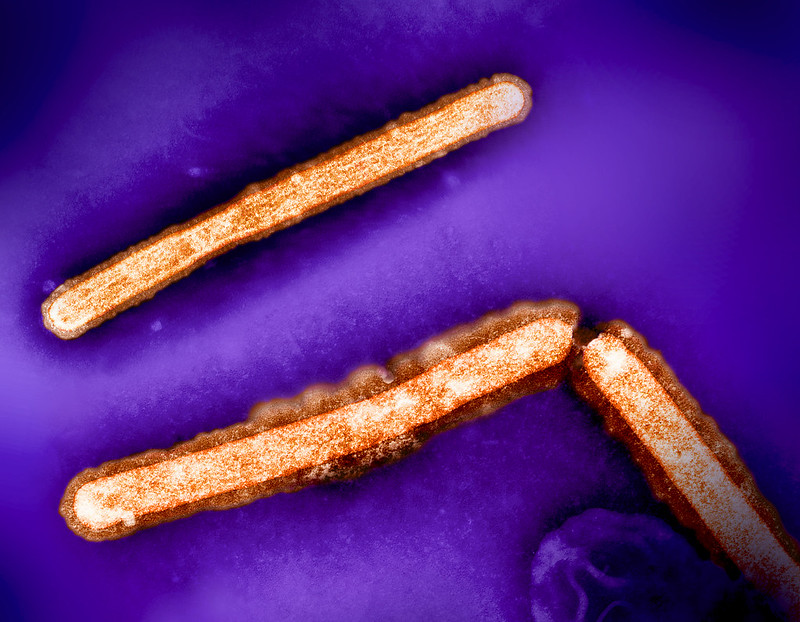

Most emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases are caused by viruses that circulate naturally in nonhuman vertebrates. "When these viruses cross over into humans, they can cause disease outbreaks, epidemics and pandemics," they authors wrote. "While zoonotic host jumps have been extensively studied from an ecological perspective, little attention has gone into characterizing the evolutionary drivers and correlates underlying these events."

Viral strains that jump species had to mutate more

About twice as many species jumps were inferred to be from people to animals rather than the other way round, a pattern consistent across most viral families. "We further observe that the extent of adaptation associated with a host jump is lower for viruses with broader host ranges," they wrote. "Finally, we show that the genomic targets of natural selection associated with host jumps vary across different viral families, with either structural or auxiliary genes being the prime targets of selection."

The genomic targets of natural selection associated with host jumps vary across different viral families, with either structural or auxiliary genes being the prime targets of selection.

In a UCL news release, lead author Cedric Tan, a PhD student at the UCL Genetics Institute, said, "When animals catch viruses from humans, this can not only harm the animal and potentially pose a conservation threat to the species, but it may also cause new problems for humans by impacting food security if large numbers of livestock need to be culled to prevent an epidemic, as has been happening over recent years with the H5N1 bird flu strain."

"Additionally, if a virus carried by humans infects a new animal species, the virus might continue to thrive even if eradicated among humans, or even evolve new adaptations before it winds up infecting humans again," he added.