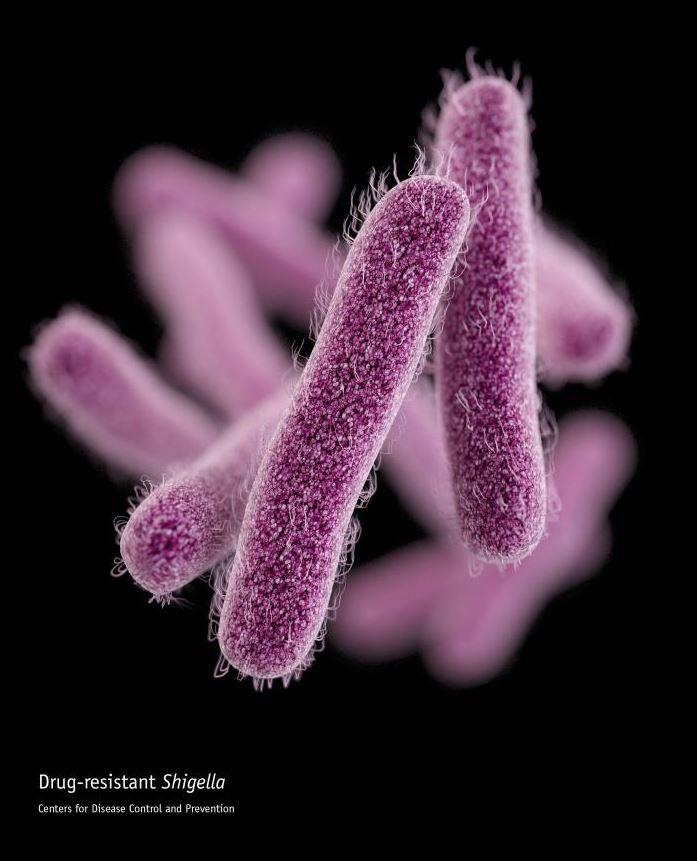

Scientists in China have for the first time identified the colistin-resistance gene MCR-1 in a species of bacteria that's one of the leading causes of diarrhea worldwide.

In a study today in Applied and Environmental Microbiology, the scientists report that they identified the gene in a single isolate of Shigella flexneri found in pig stool samples from a farm in Guangxi province. The isolate was among more than 2,000 S flexneri isolates, mostly from stool samples of patients, screened by the scientists.

Since the existence of the MCR-1 gene was first reported in Escherichia coli samples from pigs, pork products, and humans in China in 2015, it has been detected in more 30 countries. But it's mostly been found in E coli and other Enterobacteriaceae from animals and humans, mainly Klebsiella pneumoniae and Salmonella enterica. The gene has heightened concerns about antibiotic resistance because it confers resistance to a drug that is considered a last resort for treatment of infections caused by multidrug-resistant bacteria.

Another concern about MCR-1 is its mobility. Because the gene is located on mobile pieces of DNA called plasmids, it can be shared within and between different species of bacteria, which means that other multidrug-resistant pathogens can acquire resistance to colistin. This raises the specter of bacterial infections that are impossible to treat with current antibiotics.

The authors of the study say that finding the isolate in S flexneri from pig feces suggests it could be circulating on Chinese farms and beyond.

Isolate contains multiple resistance genes

The scientists screened a total of 2,127 S flexneri isolates from samples collected from 13 different areas in China. Using polymerase chain reaction (PCR), a technique that amplifies DNA sequences in bacteria, they identified one MCR-1–positive isolate, named C960. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing showed that, besides colistin, the isolate was also resistant to tetracycline, ticarcillin, ampicillin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, sulfafurazole, and streptomycin.

C960 also carried genes that could confer decreased susceptibility to quinolones and beta-lactam antibiotics. These acquired resistance genes were located on a different plasmid than the one that harbored the MCR-1 gene.

The scientists then performed conjugation experiments to see if the plasmids could be transferred to another type of bacteria when exposed to colistin, using a strain of E coli as the recipient. This revealed that both plasmids jumped to the E coli, giving it the same multidrug-resistant profile as C960.

The findings are troubling for several reasons. Although Shigella bacteria don't cause disease in animals, they are highly contagious in humans, and S flexneri is the most frequently isolated species in many countries (especially low- and middle-income countries), causing roughly 10% of all diarrheal episodes in children under the age of 5. While only one isolate was identified among pigs, the presence of a MCR-1 and other resistance genes in a pathogen that spreads quickly in humans raises significant public health concerns, given that enteric pathogens on farm animals can spill over to humans.

"Isolation of plasmid-mediated colistin-resistance in S flexneri from animal feces on a farm suggests it is circulating via the fecal-oral route at least amongst the animals on that farm and possibly further afield via the food distribution network," the authors write.

In addition, the fact that C960 transferred both of its resistance plasmids to E coli suggests that this strain of S flexneri can share and spread resistance to colistin and several other important antibiotics.

Surveillance for MCR-1

The authors say the study also suggests that the widespread use of colistin in Chinese agriculture, which has previously been linked to the emergence of MCR-1, has created enough selective pressure that other strains of MCR-1-carrying S flexneri are likely to exist on Chinese farms. And although China banned use of the drug in food-producing animals in 2016, the authors fear that use of other antibiotics on farms could co-select for these strains.

Given these concerns, they say that surveillance for MCR-1 in both environmental and clinical isolates would be advised.

Amesh Adalja, MD, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security, told CIDRAP News that, given the nature of plasmids and their tendency to proliferate into more than one species, it's not surprising to see plasmids carrying MCR-1 in other bacteria. And fortunately, he noted, Shigella infections don't always require antibiotic therapy. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, people who have shigellosis usually recover within 5 to 7 days without antibiotic treatment.

But because colistin is an important last-resort antibiotic, Adalja said that monitoring the healthcare system for more serious MCR-1-carrying pathogens is critical.

"Following MCR-1's path through clinically relevant bacteria is an important activity and underscores the need for alternative last-line agents as colistin resistance becomes more common," he said.

See also:

Mar 2 Appl Environ Micrbiol study