Decades in the making, the world's first malaria vaccine today received clearance by European drug regulators, paving the way for complex World Health Organization (WHO) deliberations on how to best use the new tool to protect African children.

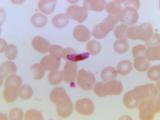

Most of the estimated 584,000 deaths from malaria each year strike children under age 4 in sub-Saharan Africa, where the burden varies by country. Unlike other infant diseases, the death risk from malaria continues through early childhood, even after repeated infection.

Large trials in Africa

The RTS,S vaccine, called Mosquirix, was developed by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and the PATH Malaria Vaccine Initiative for children ages 6 weeks to 17 months. It contains an AS01 adjuvant and is given in three doses. The vaccine has been in clinical trials since 1992, with final phase 3 trial results reported earlier this year based on findings in more than 15,000 children in seven African countries.

Andrew Witty, GSK's chief executive officer, said in a statement today that the regulatory decision is an important step toward making the first malaria vaccine available to children. "While RTS,S on its own is not the complete answer to malaria, its use alongside those interventions currently available such as bed nets and insecticides, would provide a very meaningful contribution to controlling the impact of malaria on children in those African communities that need it the most."

Studies showed that the vaccine can prevent a substantial number of infections, but protection didn't last as long as hoped. A fourth dose given as a booster appears to help with the efficacy drop-off.

Decision details

Mosquirix is the first malaria vaccine to be assessed by a regulatory agency. The positive opinion from the European Medicines Agency (EMA) Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) applies to the vaccine's use outside of the European Union.

The CHMP said the vaccine should be used based on recommendations targeted to the risk of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in different geographic regions that will be outlined by the WHO and by national authorities in the countries where it will be used.

The CHMP said that despite limited efficacy—56% in children 5 to 17 month and 31% in children 6 to 12 weeks—the benefits of vaccination outweigh the risks, and the benefits may be especially important in children in high-transmission areas where the death risks are especially high. Because the vaccine doesn't offer complete protection, other measures such as insecticide-treated bed nets should still be used alongside vaccination, the committee said.

Next steps

The EMA said the WHO will make its recommendations in November on using the vaccines in national programs. It said the WHO's recommendations will take into account factors that weren't considered by the EMA, including the feasibility of implementation, cost-effectiveness, and the vaccine's public health value when compared with other malaria prevention measures.

Two WHO committees will take up the issue: the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) and the Malaria Policy Advisory Committee.

In a press conference and e-mail briefing for journalists today, Gregory Hartl, a spokesman for the WHO, said the WHO welcomes the EMA's assessment. "This is a major milestone for malaria vaccine development, and it is one more step towards decisions as to how the vaccine will be used," he said.

So far no malaria-endemic country has licensed the vaccine, and the earliest such approval won't likely come until 2017, he said.

He said any financing for the malaria vaccine must not draw resources from bed nets, drugs, or diagnostic tests, and introducing the vaccine will require careful coordination between funding organizations.

GSK said that after the WHO makes its recommendation the company will submit an application to the WHO for prequalification of the vaccine, a scientific evaluation for any new vaccine to be added to the agency's immunization programs. The company added that the United Nations and other large vaccine procurement groups base their purchasing decisions on the WHO's prequalification decisions.

More issues to consider

In a blog post on the Global Fund Web site, two malaria experts said WHO committees have a tough task in recommending how to use the vaccine. The authors are Seth Berkley, MD, chief executive officer of GAVI Alliance, and Mark Dybul, MD, executive director of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria.

They noted that clinical trials showed only partial protection, lower than for other approved vaccines, and that it's difficult to assess the impact of Mosquirix, because other interventions such as bed nets were used at the same time. They also pointed to other unknowns, such as whether the vaccine would give people a false sense of security and whether children would get all of their doses, including a possible booster dose.

Though it might be tempting to hold off on recommending the vaccine until a better alternative comes along, Mosquirix is 5 to 10 years ahead of other vaccine candidates, and there is no guarantee others will perform any better, the experts said.

"So, if Mosquirix can potentially save lives or reduce illness now—even if only in one-in-three cases—then can we really justify holding off?"

Berkley and Dybul urged funding for proposed phase 4 studies that can help shed light on questions about effectiveness and the use of a booster dose.

See also:

Jul 24 EMA press release

Jul 24 GSK statement

Jul 24 Global Fund blog post