Researchers monitoring African bonobos have found the animals to be playing host to a previously unknown malaria parasite.

Though malarial parasites are known to be endemic in African chimpanzees and gorillas, the parasite has not been found in wild bonobos. The absence has previously been described as a mystery, because bonobos should be just as susceptible to various Plasmodium parasites as other non-human primates, and malaria has been described in captive populations of the animals.

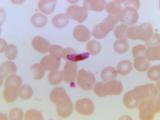

Now, by sampling more bonobos in geographically diverse settings, scientists writing in Nature Communication show that bonobos harbor a new species of malaria parasite, called Plasmodium lomamiensis. The parasite is a previously unknown Laverania species, which are closely related to P falciparum, one of the parasites that causes human malaria infections.

The researchers tested 1,556 fecal samples from 11 sites along the rain forests of the Congo Basin in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). They found high levels of Laverania in a remote area called Tshuapa-Lomami-Lualaba in the eastern part of the DRC.

"Not finding any evidence of malaria in wild bonobos just didn't make sense, given that captive bonobos are susceptible to this infection," said Beatrice Hahn, MD, a professor of microbiology in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, in a press release.

In addition to finding P lomamiensis, the researchers also isolated P gaboni, formerly found only in chimpanzees, in bonobo samples from the remote area. But they were surprised that the bonobos carrying the parasite were so geographically isolated.

"Analyses of climate data and parasite seasonality, as well as host characteristics, including bonobo population structure, plant consumption and faecal microbiome composition, failed to provide an explanation for this geographic restriction," the authors write. "Thus, other factors must be responsible for the uneven distribution of bonobo Plasmodium infections, including the possibility of a protective mutation that has not spread east of the Lomami River."

Understanding what, if any protective mutations might be guarding most African bonobos from malaria could be a key insight into how the parasite can be eliminated from human populations, the researchers wrote.

Insight into human malarial disease

Hahn and her co-authors suggest that wider testing of bonobos and all non-human primate species in Africa should be undertaken to predict how various malarial parasites could infect human populations.

"While ape Laverania parasites have not yet been detected in humans, it seems clear that the mechanisms governing host specificity are complex and that some barriers are more readily surmountable than others," the authors write. "Given the new bonobo data, it will be critical to determine exactly how P. praefalciparum was able to jump the species barrier to humans, in order to determine what might enable one of the other ape Laverania parasites to do the same."

See also:

Nov 21 Nat Commun study

Nov 21 University of Penn press release