From 1970 to 2021, mpox cases were detected year-round in equatorial Africa but were detected seasonally in tropical regions in the Northern Hemisphere, finds an analysis of 133 zoonotic index cases led by Institut Pasteur researchers in Paris.

Published in Emerging Infectious Diseases, the study was based on peer-reviewed and "gray" (alternatively published) literature on index mpox cases of zoonotic origin in Africa over the 50-year timeframe. The team also used remotely sensed meteorologic, topographic, climate, seasonality, environmental, land use–land cover, and fire data.

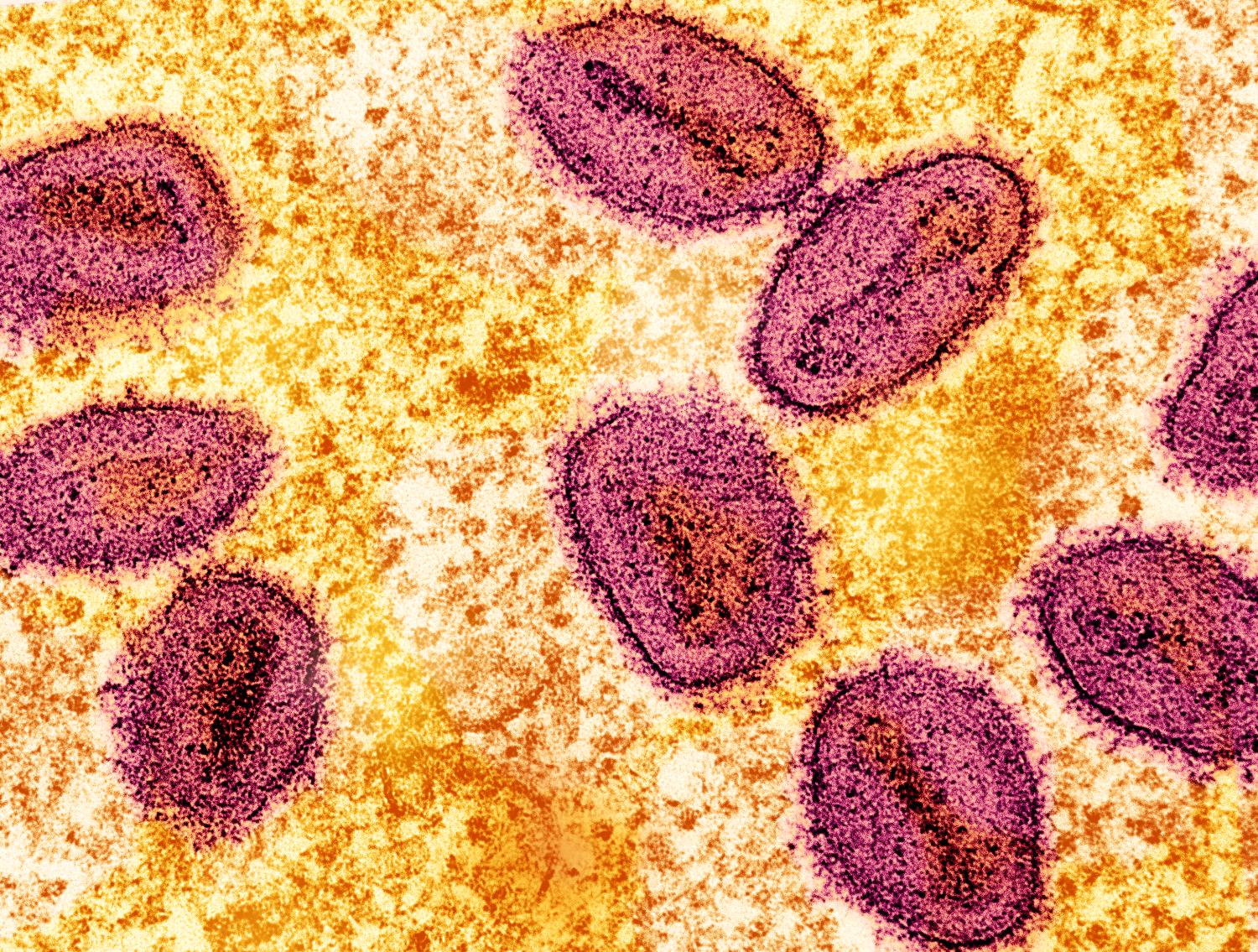

"Mpox, caused by monkeypox virus (MPXV), remains a neglected tropical zoonotic disease of forested Central and West Africa," the authors wrote. "Mpox epidemiology is poorly understood, and the MPXV animal reservoir remains unknown."

Climate change could worsen seasonal drivers

Of 133 index cases from 113 sites, 64% were reported in 2000 and later, 86% were the Congo Basin/clade 1 virus, and 13% were West African/clade 2. The Democratic Republic of the Congo accounted for 44% of cases, and the Central African Republic accounted for 33%.

Determining whether specific seasons or periods bring greater risk for human transmission can improve prevention and surveillance initiatives and contribute to identifying animal reservoirs.

Cases were identified at a median latitude of 3.44°N and varied significantly by month. Most infections occurred at lower latitudes from January to July (not including April) but were seen mainly at higher latitudes from August to December. Index cases were primarily identified in equatorial cool (33%), northern cool wet-dry (35%), and northern hot wet-dry climates (17%).

The researchers noted a potential high-risk season from August to March, which spans the last 3 months of the rainy season and the entire dry season. "That finding suggests complex drivers likely related to human and wildlife ecology," they wrote. "Various seasonal activities can increase human contact with wildlife."

Climate and environmental changes could worsen seasonal drivers of human MPXV exposure, the authors said: "Determining whether specific seasons or periods bring greater risk for human transmission can improve prevention and surveillance initiatives and contribute to identifying animal reservoirs. For this, a genuine One Health approach is crucial."