Jan 18, 2008 (CIDRAP News) – The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) this week charged that federal pandemic planning efforts rely too heavily on law enforcement and national security approaches, in effect making people, not disease, the enemy.

The ACLU aired its concerns in a report authored by three prominent public health law attorneys and released Jan 14 at a press conference in Washington, DC. The authors are George Annas and Wendy K. Mariner from the Boston University School of Public Health and Wendy E. Parmet of Northeastern Law School.

The report discusses a wide range of privacy protections and other civil liberties that the ACLU believes might be threatened in a pandemic setting. The authors include a list of recommendations intended to focus pandemic planning efforts more toward community engagement, as well as an appendix that covers a number of constitutional issues that could surface during a pandemic.

"A law enforcement approach is just the wrong tool for the job when it comes to fighting disease," said Barry Steinhardt, director of the ACLU's technology and liberty program, in a Jan 14 press release. He said history shows that a coercive approach to pandemic that treats sick people as enemies is ineffective from a public health perspective.

But a spokesman for the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) says the group has mischaracterized the government's efforts. Also, other critics with expertise in public health and the law say the ACLU report is marred by a misunderstanding of government response plans.

In the past, President George W. Bush has suggested that federal officials may need to quarantine regions of the country if localized outbreaks of pandemic flu occur, according to previous reports. In October 2005, he suggested expanding presidential power over state-run National Guard operations to implement quarantines during a pandemic.

Bush said that such executive power during a pandemic was an important topic for Congress to debate, according to a previous CIDRAP News report. "Congress needs to take a look at circumstances that may need to vest the capacity of the president to move beyond that debate. And one such catastrophe, or one such challenge, could be an avian flu outbreak," he said at an Oct 4, 2005, press conference.

In April 2005, Bush signed an executive order that authorized adding pandemic influenza to a federal list of diseases that can lead to quarantine.

All-hazards approach critiqued

The ACLU authors assert that an all-hazards approach to disaster planning—one based on the assumption that the same preparedness model can be applied to any kind of disaster, whether biological, chemical, explosive, natural, or nuclear—has steered federal officials into assuming worst-case scenarios. "All of the plans rely heavily on a punitive approach and emphasize extreme measures such as quarantine and forced treatment," they wrote.

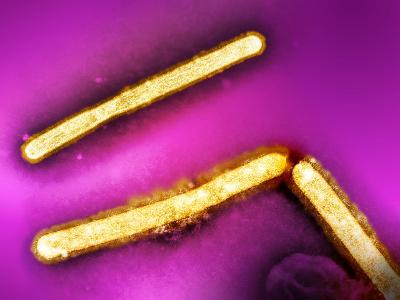

As a recent example, the attorneys pointed to the events of last spring when the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued its first domestic isolation order in 40 years for Atlanta attorney Andrew Speaker, who was traveling abroad when tests suggested he had extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR TB). They wrote that the CDC's order prompted Speaker to take evasive actions that could have exposed other travelers. "In the case of an epidemic, the same evasive behavior seen here in one man would likely be replicated on a mass scale that would undermine the goal of stopping the disease," the ACLU report states.

The report also raises concerns over the October 2007 presidential directive on public health and medical preparedness, which establishes a prominent role for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in public health disaster management, incorporates Department of Defense expertise and resources into disaster management, and calls for a national biosurveillance system. The ACLU argues that a biosurveillance system that is too broad could erode the privacy of all patients.

"More ominously, the participation of military and homeland security officials in this public health venture raises questions about how the information will be used," the authors wrote.

HHS says report is off target

However, HHS spokesman Bill Hall told CIDRAP News that the ACLU experts have misunderstood the federal government's pandemic plans. They have focused too much on containment efforts that the government may or may not use to stamp out the virus in a local area at the earliest stage of a pandemic, he said. Some pandemic flu experts have said containment shouldn't even be attempted at the early stage, because they doubt such an effort would work, Hall said.

Government officials solidly support voluntary quarantine as an effective community mitigation strategy, he said. "SARS [severe acute respiratory syndrome] was a public health success story," Hall said. "But the word 'quarantine' conjures up images of soldiers and a police state that are hard images to get out of people's minds."

Michael T. Osterholm, PhD, MPH, said he doesn't think health officials will be able to contain an emerging pandemic and that the ACLU report misses the mark because it doesn't seem to consider aspects of the federal plan outside of initial containment. "Is this a law enforcement based approach? It's not, no way," said Osterholm, who is director of the University of Minnesota Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, publisher of CIDRAP News.

However, Osterholm said he agrees with the ACLU's criticism of the government's emphasis on an all-hazards approach to disaster preparedness. Planning for a pandemic presents many unique challenges, he said. For example, the long duration of a severe pandemic, unlike a disaster such as the 9/11 terrorist attacks, would lead to a collapse of the nation's just-in-time economy, Osterholm said.

Steven Gravely, a public health law expert who is a partner and head of the healthcare practice group at Troutman Sanders, a law firm in Richmond, Va., said he doesn't think the ACLU report is a fair assessment of the nation's pandemic planning efforts. "It focuses too much on the federal level and doesn't recognize that disaster response—pandemics, particularly—is handled by several governments: local, state, tribal, federal, and international," Gravely told CIDRAP News.

"What jumped out at me is their discussion of quarantine and isolation," he said. "Though they characterize the federal plan as militaristic, 95% of isolation and quarantine is done at the state level. Federal involvement in quarantine is extremely limited."

Even in the Andrew Speaker case, the federal isolation order was in force for just a few days, and then the state of Colorado took over, Gravely said.

State emergency powers cause concern

The ACLU report raises concern about CDC support for a Model State Emergency Powers Act, drafted after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, describing it as a tool for states to broaden isolation and quarantine powers in a public health emergency. "The Act used fear to justify methods better suited to quelling public riots than protecting public health," the experts wrote.

Gravely commented in response, "I think what the ACLU report misses is that every state in the union had quarantine laws before 9/11. Some older laws were exceptionally broad or ineffective. But some changes have actually put limits on the laws." For example, he said Virginia amended its quarantine law to incorporate some of the concerns raised by the ACLU experts, such as by providing that quarantine powers take effect only when other measures fail and that patients have a right to legal counsel.

"Most states, as they updated their laws, incorporated due process," Gravely said.

Gravely said he applauded the ACLU report, "but it would have been more useful if it reflected the reality." For example, the report implies that an all-hazards approach to federal disaster planning has side-stepped pandemic-specific needs, he said. However, he observed that the community mitigation guidance HHS issued for states adjusts nonpharmaceutical interventions according to pandemic severity.

Medical privacy issues raised by the ACLU experts are important, Gravely said. "They have captured that we need to be vigilant in balancing privacy in broad-based surveillance."

Gravely said a major overhaul of medical privacy legislation in 1996 that produced the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) contains a number of exceptions to privacy protections, one of which is public health reporting. Concern about how states will use medical surveillance information is a valid policy issue, but there is no evidence that states are misusing such information, he said.

Hall said the ACLU's recommendations include several items the federal government is already working on. One example is the pandemic vaccine prioritization draft plan, on which federal officials have held town hall forums and sought extensive public feedback.

Some of the ACLU's other pandemic preparedness recommendations include:

- Developing rapid, accurate diagnostic tests to reduce errors in identifying people who have infectious diseases

- Focusing on community engagement for pandemic preparations rather than individual responsibility

- Providing food, medicine, and supplies to people who stay home during a pandemic

- Detaining individuals, when absolutely necessary, in medical facilities rather than correctional facilities

- Ensuring due process and the right to legal counsel for individuals who are proposed for isolation or restricted from travel.

See also:

Jan 14 ACLU press release

Jan 14 ACLU report on pandemic preparedness

Oct 4, 2005, CIDRAP News story "Bush suggests military-enforced quarantines for avian flu"

Oct 22, 2007, CIDRAP News story "White House aims to transform public health preparedness"

Feb 1, 2007, CIDRAP News story "HHS ties pandemic mitigation advice to severity"