Feb 2, 2006 (CIDRAP News) A pair of new studies suggest that influenza vaccines based on adenoviruses, one of the causes of the common cold, may offer major advantages in the quest for protection from flu pandemics.

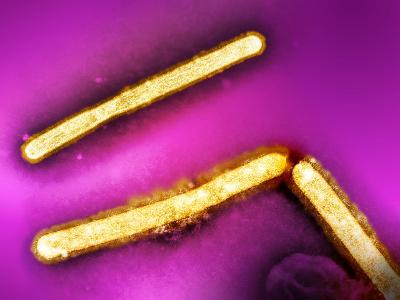

In both studies, scientists manipulated adenoviruses to duplicate a key protein (hemagglutinin) found in H5N1 avian flu viruses and then injected the engineered viruses into mice. The vaccines generated an immune response that protected the mice when they were exposed to high doses of H5N1 viruses, including strains that did not precisely match the strains from which the hemagglutinin was derived. In one of the studies, the vaccine also protected chickens.

The reports raise hopes that pandemic flu vaccines could be produced in cell culture, saving time compared with the months-long process of growing them in chicken eggs. In addition, because the experimental vaccines seemed to offer broader protection than conventional egg-based vaccines do, it may be possible to produce and stockpile a pandemic vaccine in advance instead of waiting until a pandemic virus emerges, the reports say. However, the vaccines have not yet been tested in people.

"This approach is a feasible vaccine strategy against existing and newly emerging viruses of highly pathogenic avian influenza to prepare against a potential pandemic," states one of the reports, published online by The Lancet. "This approach also provides a viable option for potential vaccine stockpiling for the influenza pandemic." The report was prepared by a team from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Purdue University, with Mary A. Hoelscher as the first author.

The other study was conducted by a team from the University of Pittsburgh, the CDC, and the US Department of Agriculture's Southeast Poultry Research Laboratory, with Wentao Gao as the first author.

"Our findings as well as those from other adenovirus-based vaccine studies support the development of replication-defective adenovirus-based vaccines as a rapid response in the event of the pandemic spread" of avian flu, write Gao and colleagues in the Journal of Virology.

In the CDC-Purdue study, researchers made a vaccine consisting of a nonreplicating adenovirus containing the hemagglutinin gene from an H5N1 virus identified in Hong Kong in 1997. One group of mice was injected with this vaccine, while other groups were injected with saline solution or one of two other control vaccines.

Four weeks after their second injection, the mice were given high doses of one of two H5N1 virus strains, including a Hong Kong 1997 strain (but not the same one as used to make the vaccine) and a 2004 variant from Vietnam. All the mice that received the experimental vaccine survived with minimal illness as measured by weight loss.

The researchers also took blood samples from the vaccinated mice and assessed the serologic response to three different H5N1 virusesthe 1997 strain used in the vaccine, plus 2003 and 2004 strains from Hong Kong and Vietnam, respectively. The experimental vaccine produced a "significantly high" antibody response to the 1997 virus but weaker responses to the other two viruses.

To assess cellular immune responses, the researchers measured the generation of CD8 T-cells in the vaccinated mice. Mice that received the experimental vaccine had a three-fold to eight-fold higher frequency of CD8 cells than those that received control vaccines, a significant difference.

The results showed that the experimental vaccine effectively protected mice "from H5N1 disease, death, and primary viral replication" after exposure to "antigenically distinct strains of H5N1 influenza viruses," the authors write. "This strategy has the advantage of inducing strong humoral and cellular immunity and conferring cross-protection against continuously evolving H5N1 viruses without the need of an adjuvant," they add.

The study's senior author, Suryaprakash Sambhara of the CDC, said the adenovirus-based vaccine can be made much more quickly than conventional flu vaccines, according to a Reuters report published today.

In the Pittsburgh study, researchers engineered an adenovirus to duplicate hemagglutinin from a 2004 Vietnam strain of H5N1 virus. They injected this into mice and then exposed them to an H5N1 virus 70 days later. The mice were fully protected by the vaccine, which generated both hemagglutinin-specific antibodies and a cellular immune response.

The experimental vaccine was also tested in chickens by giving them a single subcutaneous dose and exposing them to H5N1 virus 21 days later. The immunized chickens were fully protected, while a group of unvaccinated chickens all died.

The authors write that their results indicate that widespread use of adenovirus-based vaccines in poultry would probably help stop the spread of highly pathogenic avian flu. And in the case of a human flu pandemic, they add, "an adenovirus-based vaccine could be utilized to complement traditional inactivated influenza virus vaccine technology, which is still the primary choice," despite the limitations of egg-based production.

Hoelscher MA, Garg S, Bangari DS, et al. Development of adenoviral-vector-based pandemic influenza vaccine against antigenically distinct human H5N1 strains in mice. Lancet 2006 (published online Feb 2) [Abstractaccess requires free registration]

Gao W, Soloff AC, Lu X, et al. Protection of mice from lethal H5N1 avian influenza virus thorugh adenovirus-based immunization. J Virology 2006 Feb;30(4):1959-64 [Abstract]

See also:

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center news release

http://www.upmc.com/MediaRelations/NewsReleases/2006/Pages/GambottoAvianFluStudy2006.aspx